“Photo of the Chinese lion dancers taken at the Pershing Chinese marker rededication ceremony at JBSA-Fort Sam Houston, Texas, March 25, 2023. (U.S. Air Force photo by Nelson James.)”

Credit: Joint Base San Antonio via Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain)

Grade: 6-9Subject:

U.S. History, Social Studies, English Language Arts

Number of Lessons/Activities: 4

In 1916, General John Pershing (1860-1948) led the Mexican Punitive Expedition to pursue Mexican revolutionary leader Pancho Villa (1878-1923). Pershing recruited hundreds of Chinese in Texas and Mexico to support the expedition, who became known as “Pershing’s Chinese.” When the expedition ended in 1917, Pershing returned with 524 Chinese men. In this lesson, students will learn about the history of Pershing’s Chinese and how they came to the United States. Students will also examine how Pershing’s Chinese were allowed to stay in the United States during the era of Chinese Exclusion.

Students will:

- Describe the historical events that led Pershing’s Chinese to settle in Texas.

- Analyze letters written by General Pershing that allowed Pershing’s Chinese to gain permanent residency in the United States.

- Explain how Pershing’s Chinese were an exception to the Chinese Exclusion Act.

Pershing’s Chinese Essay:

One special exception to this period of Chinese exclusion was the case of Pershing’s Chinese. In 1916, Pancho Villa (1878-1923), the Mexican revolutionary and political leader, crossed the U.S.-Mexico border. Following a military defeat by his rival, Venustiano Carranza (1859-1920), the U.S. government officially recognized Carranza as the president of Mexico. Villa saw this as a betrayal. He attacked U.S. soldiers and civilians in Columbus, New Mexico. In response, President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) organized the

Mexican Punitive Expedition (1916-1917). It was led by General John Pershing (1860-1948). Pershing was tasked with pursuing Villa into Northern Mexico and capturing him.

Pershing was given about 7,000 soldiers but little logistical support. He placed an advertisement in local Texas newspapers. Hundreds of Chinese in Texas responded. They were put to work building a supply line for the expedition. First, they cleared brush for camps. Then, they prepared food and

potable water for the soldiers. These men became known as “Pershing’s Chinese.”

Once the expedition entered Mexico, hundreds of Chinese immigrants living in Mexico joined the expedition. They became part of Pershing’s Chinese. They provided services and goods such as laundry, tobacco, and soap. They were also able to source

provisions from local communities when supply lines were disrupted. In one recorded instance, the Chinese even fought against Villa’s forces.

Anti-Chinese sentiment in Mexico drove the Chinese immigrants to join the expedition. For as long as the Chinese had been migrating to the United States, they had also been migrating to Mexico (primarily the northern states) as laborers. At the start of the 20th century, many Chinese in Mexico transitioned into

commercial and service industries. Many Mexicans resented the Chinese for their growing wealth. When the Mexican Revolution began in 1910, revolutionary forces, including Villa, assumed an anti-immigrant stance. They accused Chinese immigrants of exploiting the local people.

The Punitive Expedition ended with Pershing unable to capture Pancho Villa. In 1917, President Wilson called the expedition home due to the looming threat of World War I (1914-1918). There were also fears of a larger war with the Mexican government. Pershing returned with 524 Chinese men in tow who had assisted the expedition. They insisted on following him, fearing a

reprisal from Villa. Up to this point, the U.S. government had developed an informal policy of housing Chinese

refugees fleeing violence in Mexico at the border. They were granted an early form of temporary

asylum. However, they were not allowed to enter the United States. This would violate the Chinese Exclusion Act in effect. And so, Pershing interceded on his men’s behalf and negotiated an initial

compromise. In this agreement, the Chinese would be held under military

supervision until it was safe for them to return to Mexico. They would later be transferred to Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas and other nearby military bases. There, they were allowed to continue working for the military in service roles. They cooked for workers constructing Camp Kelly, a new army training center. They worked in warehouses and laundries. They also took on jobs for the military such as carpenters and blacksmiths.

In 1921, Congress passed Public Resolution 29, granting

permanent residency to the remaining Pershing’s Chinese. About half of the Pershing’s Chinese stayed in San Antonio. They started businesses such as groceries and restaurants. Their children attended local schools. The Chinese community founded their own church. They started a Chinese School in 1928 to preserve their language and culture. Many of the men would marry Mexican women. By 1940, the San Antonio Chinese community became the largest in Texas. After Congress repealed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943, the Pershing’s Chinese applied for citizenship. Today, many of the descendants of the Pershing’s Chinese remain in Central Texas.

Bibliography:

James, Gregory. "Pershing’s Chinese: the Other Chinese Labour Corps."

Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch, vol. 58, 2018, pp. 189-207,

https://www.jstor.org/stable/26531709. Accessed 16 June 2025.

Urban, Andrew. "Asylum in the Midst of Chinese Exclusion: Pershing’s Punitive Expedition and the Columbus Refugees from Mexico, 1916–1921." Journal of Policy History, vol. 23, no. 2, 2011, pp. 204-229.

- Asylum: protection given especially to political refugees

- Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882: law that severely restricted the entry of Chinese to the United States and excluded Chinese people from becoming citizens**

- Citizen: a native or naturalized person who owes allegiance to a government and is entitled to protection from it

- Commercial: relating to the buying and selling of commodities on a large scale involving transportation from place to place

- Compromise: a settlement of a dispute by each party giving up some demands

- Expedition: a journey undertaken by a group of people with a particular purpose like war

- Mexican Punitive Expedition: a military operation conducted by the U.S. Army led by General John Pershing against Pancho Villa, from 1916-1917; also known as the Pancho Villa Expedition or the Mexican Expedition

- Page Act of 1875: law that prohibited the entry of Chinese women to the United States**

- Permanent resident: person living in the United States under legally recognized and lawfully recorded permanent residence as an immigrant. Also known as “permanent resident alien,” “resident alien permit holder,” and “Green Card holder.”*

- Potable: suitable for drinking

- Provisions: a stock of materials or supplies

- Punitive: inflicting or intended as punishment

- Refugee: a person who flees to a foreign country or power to escape danger or persecution

- Reprisal: the use of force short of war by one nation against another in return for damage or loss suffered

- Supervision: the act of being in charge of

- What was the Mexican Punitive Expedition? Why was it “punitive”?

- Who were “Pershing’s Chinese” and why are they called that?

- What types of support did Pershing’s Chinese provide to General Pershing’s expedition?

- Why did Chinese immigrants in Mexico join the expedition? What roles did they play?

- How did the Punitive Expedition end?

- Why did Pershing’s Chinese want to stay with General Pershing?

- How did General Pershing intercede on behalf of the Pershing’s Chinese?

- How did the Pershing’s Chinese found the Chinese American community in San Antonio?

- How is the story of Pershing's Chinese an exception to the era of Chinese exclusion?

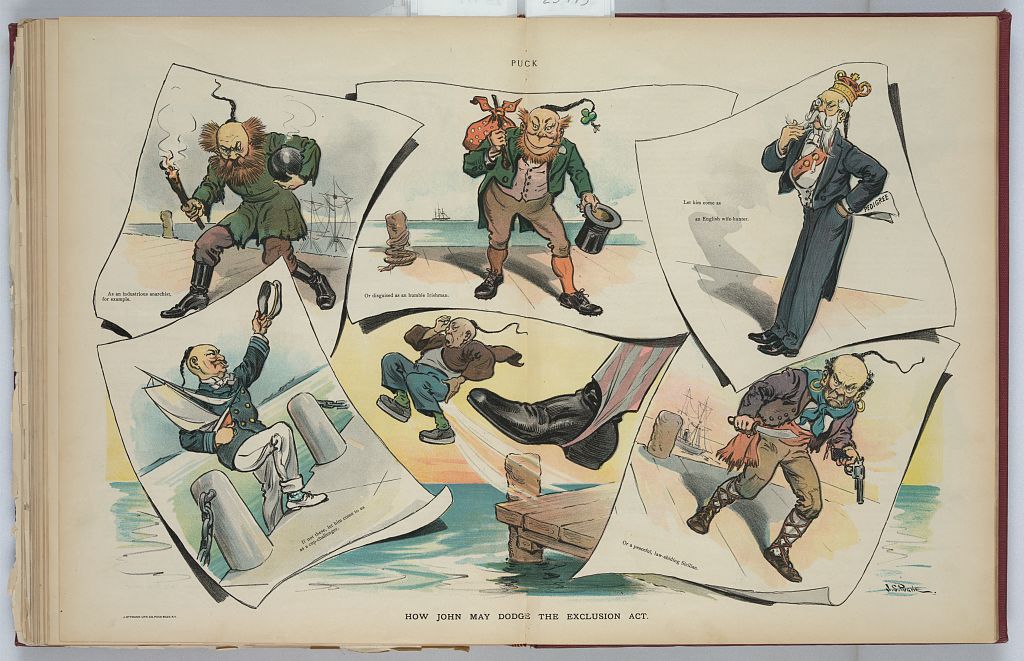

Political cartoons like this one were common during the era of Chinese exclusion. This illustration shows Uncle Sam’s boot kicking a Chinese immigrant off a dock as part of an anti-Chinese immigration campaign.

Credit: “How John may dodge the exclusion act” by J.S. Pughe. Library of Congress. No known restrictions on publication.

Activity 1: Building Background on Exclusion Era

- Show students a clip (0:00-6:43) from the video entitled, “Exclusion: The Shared Asian American Experience .”

- Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- Why were Asians excluded from the United States during the 19th and 20th centuries?

- What was the Chinese Exclusion Act? What were its impacts?

- Tell students the following: “Chinese and other Asians were largely excluded from immigrating to the United States or becoming citizens from 1875 to 1965. There were some exceptions to exclusionary laws. One such example is Pershing’s Chinese, who largely settled in San Antonio, Texas.”

Activity 2: Learning About Pershing’s Chinese

- Have students read the essay. Consider the following options:

- OPTION 1: Have students read the essay independently either for homework or during class time.

- OPTION 2: Read aloud the essay and model annotating.

- OPTION 3: Have students read aloud in pairs or small groups.

- Facilitate a class discussion by asking students the Discussion Questions.

- Show students the video entitled, “Pershing's Chinese descendants take pride in their history.”

- Facilitate a discussion about the video by asking the following questions:

- What new information did you learn?

- Why is this history largely unknown?

- Why is it important to learn from the descendants of the Pershing’s Chinese?

- What is the significance of the historic marker in Fort Sam Houston?

General John Pershing

Credit: Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain)

Activity 3: Examining General Pershing’s Letter

- Tell students the following: “Congress passed Public Resolution 29 in 1921, granting permanent residency to the remaining Pershing’s Chinese. This legislation was debated in Congress. Recall that public opinion was very anti-Chinese at this time. Numerous laws were in place that excluded Chinese people from citizenship and immigration. Anti-Chinese sentiment was common. Given this context, why did Congress make an exception to the Chinese Exclusion Act by allowing Pershing’s Chinese to stay?”

- Distribute the worksheet entitled, “Primary Source Analysis of Pershing's Letters.” Have students read two letters written by General Pershing to members of Congress in support of the Chinese refugees on pages 1-3 of the worksheet.

- Have students work in pairs to complete the Primary Source Analysis on page 4 of the worksheet:

- Have students complete the analysis for Letter #1 in the middle column, and Letter #2 in the right column.

- Have students add sourcing information in “Part 1: Sourcing.”

- Type of document

- Author

- Date created

- Audience: Who is meant to read this document?

- Have students summarize the letter in “Part 2: Summarizing.”

- Message: What is the document about and what information does it provide?

- Have students analyze the letter in “Part 3: Analyzing.”

- Purpose: Why did the author create this document? What was their goal?

- Language: What word choice, phrases, tone, etc. does the author use to communicate their message?

- Evidence: What evidence does the author use to make their argument?

- Facilitate a discussion about Pershing’s letters by asking the following questions:

- What argument is Pershing making?

- What evidence does he provide? Do you find his evidence compelling?

- Do you agree with his argument? Why or why not?

- How does Pershing’s status (a White male, American citizen and high-ranking military official) give his letters authority?

- What are the complexities of referring to this group as “Pershing’s Chinese”? How is this problematic? How is it advantageous?

- Why was Pershing’s support necessary in this case?

- What was Pershing’s motivation in helping the Chinese?

“A group photo is taken of the relatives of the immigrant workers and guests of honor at the Pershing Chinese marker rededication ceremony at JBSA-Fort Sam Houston, Texas, March 25, 2023. (U.S. Air Force photo by Nelson James.)”

Credit: Joint Base San Antonio via Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain)

Activity 4: Explaining the Exception to Chinese Exclusion

- Have students write an essay addressing the following questions:

- What was the impact of the Chinese Exclusion Act on the Pershing’s Chinese?

- Why was an exception made to the Chinese Exclusion Act to allow the Pershing’s Chinese to stay in the United States?

- Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- How was the Chinese Exclusion Act an unfair and racist law?

- Under what circumstances do people have a responsibility to challenge unfair and racist laws?

- Have students research the San Antonio Chinese American community, including its history, demographics, important landmarks, organizations, etc.

- Have students read the historical marker for the Pershing Chinese, located in Fort Sam Houston in Bexar County, Texas. Have students discuss the significance of historical markers. Have students create a historical marker for a site of significance to them.