Audience members wave the flag of Cambodia and enjoy performances by Cambodian and Cambodian American artists at the Inaugural Cambodia Day in San Francisco in September 2024.

Credit: Copyright © The Asian American Education Project

Grade: 9-12Subject:

History, Social Studies, Ethnic Studies

Number of Lessons/Activities: 4

The Cambodian rock music scene was booming in the 1960s and 1970s. Western, Latin American, and Afro-Cuban pop music became popular in Cambodia and influenced Cambodian musicians. They created a distinctive style of music that mixed traditional Khmer instruments and sounds with modern and foreign influences. The Cambodian rock era came to an abrupt end when the communist Khmer Rouge came to power in April 1975. In this lesson, students will learn about the history of Cambodian rock music and the factors that led to its rise - including the rediscovery of Cambodian rock from the 1990s to present, focusing on contemporary Cambodian American musicians.

Students will:

- Examine the history of Cambodian rock music in the 1960s and 1970s.

- Identify the influences on the development of Cambodian rock music.

- Analyze the impact of Cambodian history on contemporary Cambodian American artists.

Cambodian Rock Music Essay:

Cambodia gained independence in 1953, after nearly a century of French

colonial rule (1863-1953). King Norodom Sihanouk (1922-2012) assumed leadership of the country. A film director, painter, and musician, Sihanouk was an influential supporter and patron of the arts. During these early years of independence under Sihanouk’s reign, music in Cambodia flourished.

Artists and others in Cambodia wanted to create a sense of national identity. The 1950s to mid-1970s is often referred to as the “Golden Era” of music in Cambodia. During this time, clubs, bars, and live music venues prospered in Phnom Penh, the capital of Cambodia, and spread to other cities. People began to have more

disposable income, which they could spend on music and fun.

Several factors contributed to the growing influence of international music on Cambodian musicians. First, wealthy Cambodians traveled to France and brought back Western pop records. They also imported Afro-Cuban and Latin American records. Second, Cambodian civilians were increasingly exposed to Western music through the

U.S. Armed Forces Radio. The U.S. military was gradually increasing its presence in nearby Vietnam; as such, Western music was broadcasted to troops.

By the early 1960s, some Cambodian musicians began to combine traditional Cambodian music with pop, rock and roll, and

psychedelic music from other parts of the world. As such, Western, Latin American, and Afro-Cuban pop music became popular in Cambodia and influenced Cambodian musicians. Cambodian musicians created a distinctive style of music that mixed traditional Khmer instruments and sounds with modern and foreign influences.

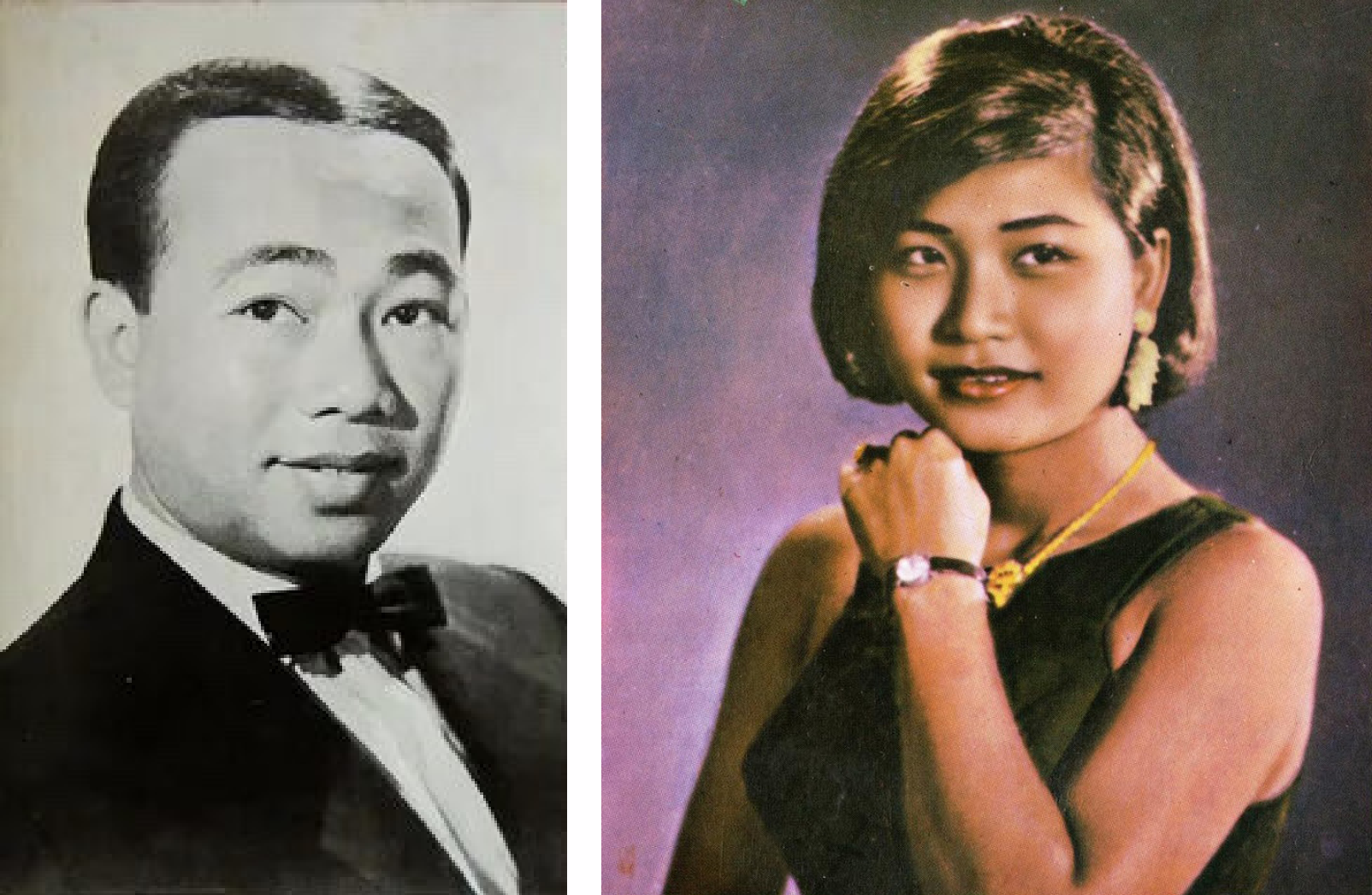

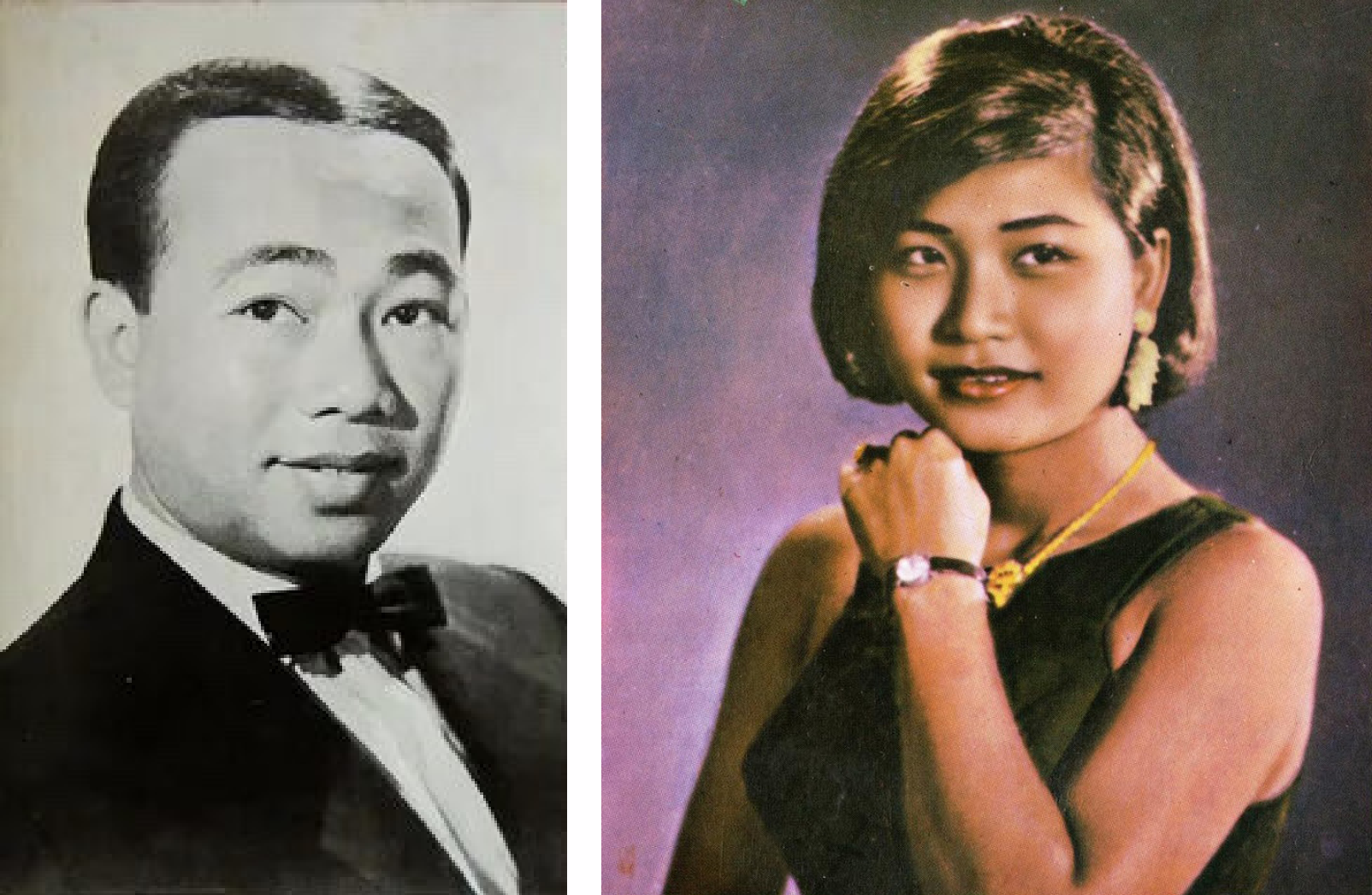

The Cambodian rock scene was booming in the 1960s and 1970s. Sinn Sisamouth (1933-1976) was one of Cambodia’s most famous musicians. He embraced and adapted Western musical styles with Cambodian music and became known as the “Elvis of Phnom Penh” and the “King of Khmer Music.” This was a reference to the famous American singer Elvis Presley (1935-1977), known as the “King of Rock and Roll.”

Ros Serey Sothea (1948-1977) was another famous singer who embraced rock music and recorded over one hundred songs. She was known for her distinctive vocals and was called the “Queen with the Golden Voice.” Another leading artist in the rock scene was Yol Aularong,* who was known for his rebellious and original music. In 1959, two teenage brothers Mol Kagnol* and Mol Kamach,* formed Baksey Cham Krong, which many consider to be Cambodia’s first rock band. In 1967, the band Drakkar formed. They were greatly influenced by popular Western bands like The Beatles and The Rolling Stones. These musicians, and many others, dominated a short but thriving era of rock music in Cambodia.

This musical era began to die down during the Cambodian Civil War (1967-1975), amidst U.S. bombings of Cambodia. While the bombings were intended to deter the rise of

communist forces in Cambodia and Vietnam, between 150,000 to 500,000 civilians were killed. People became afraid to go out in public, and

curfews were imposed in Phnom Penh. For some time, the National Radio of Cambodia only allowed

patriotic songs to be played.

The Cambodian rock era came to an abrupt end when the communist Khmer Rouge, a guerilla military force, came to power in April 1975. The Khmer Rouge’s four-year regime was characterized by terror and

totalitarianism. They killed former military and government officials and anyone they considered to be a

dissident. Their goal was to turn Cambodia into a rural

agrarian society. Under the Khmer Rouge regime, an estimated 1.5 to 2 million people, roughly a quarter of the country’s population, were killed in what came to be called the Cambodian Genocide.

The Khmer Rouge regime saw most musicians as a threat. They believed modern music, especially with foreign influences, was incompatible with the agrarian society they envisioned. Totalitarian regimes have often feared music for its ability to spread dissidence. Music can also be used as

propaganda. The regime carefully controlled music in an effort to instill a sense of new identity and loyalty to the Khmer Rouge. Music that did not not support the regime was banned, recordings were destroyed, and musicians and other artists disappeared. Many musicians are believed to have been executed by Khmer Rouge soldiers. Some recordings however survived in fans’ personal collections, but by 1979, much of Cambodian rock music was lost.

Many of the survivors of the Khmer Rouge regime fled to other countries. For example, from 1975-1994, about 150,000 Cambodians arrived in the United States as

refugees. Since then, the population of Cambodian Americans has continued to grow, with over 300,000 Cambodian Americans living in the United States in 2000.

Despite the growing population, Cambodian rock of the 1960s and ‘70s was largely unknown in the United States until the 1990s. In 1994, an American tourist purchased cassette tapes from market vendors in Cambodia and put together a mixtape. This later became a compilation of twenty-two Cambodian rock songs in an album called Cambodian Rocks (1996), which later inspired the documentary film Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten: Cambodia’s Lost Rock and Roll (2014). The film explores the history of Cambodian rock music of the 1960s and ‘70s and how it was impacted by the Khmer Rouge regime.

The band Dengue Fever also facilitated the rediscovery of Cambodian rock in the United States. In 1997, keyboardist Ethan Holtzman,* a White American, heard Cambodian rock music while traveling in Cambodia and brought back several cassette tapes. He and his brother Zac Holtzman,* a guitarist and singer who separately learned of Cambodian rock from a friend, formed Dengue Fever in 2001. The Holtzman brothers recruited Chhom Nimol (born 1980) to be the lead singer. Nimol is a Cambodian American refugee who came from a family of well-known musicians in Cambodia. She sings the lyrics to the band’s songs in Khmer. Dengue Fever’s first album is mostly covers of Cambodian rock music from the 1960s and ‘70s, including songs by artists like Sisamouth and Sothea. Later albums are mostly original songs.

For some younger generations of Cambodian Americans, music can be a way of learning about Cambodian history and culture. Many Cambodian American refugees were traumatized by the Cambodian Genocide, making it hard to talk about their experiences with their children. Young Cambodian American musicians are connecting over social media or through friends and family to make music together, while also learning about their history.

A new generation of artists has since emerged, building on the Cambodian rock scene of the 1960s and 1970s. Bochan Huy* was born in Phnom Penh, Cambodia and fled to the United States with her family as a child. Her father, Chhan Huy,* was an engineer and rock musician. Bochan Huy is a singer and songwriter who combines traditional Khmer music with classic Cambodian rock, hip hop, and soul music to create her own musical style. Laura Tevary Mam (born 1986) is a Cambodian American singer and songwriter who also blends Khmer and Western music styles. She is known as one of the artists who started the Cambodian Original Music Movement, a movement of Khmer musicians who create new and original music in Cambodia post-Khmer Rouge. She and her mother, Thida Buth,* also founded a production company in Cambodia called Baramey Productions.

In 2016, playwright Lauren Yee’s*

Cambodian Rock Band debuted. This play, which tells the story of a Cambodian American woman and her father who survived the Khmer Rouge regime, features Cambodian rock music from the 1960s and ‘70s, as well as more contemporary hits from Dengue Fever. In 2023, Cambodian American rapper PraCh Ly* wrote and directed a show called

Khmeraspora with the Long Beach Symphony. Long Beach, California has the largest population of Cambodians outside of Cambodia. The show tells the story of Cambodian American refugees, from leaving Cambodia to

resettling in the United States.

There are some tensions around this rebirth of Cambodian rock in the United States. Any references to pre-war Cambodia or the Khmer Rouge regime can bring back painful memories to survivors. As Cambodia began to rebuild after the Khmer Rouge regime, much of the emphasis was on preserving and protecting Khmer cultural traditions. With the rebirth of Cambodian rock, musicians are moving away from “traditional” music and blending it with more modern influences, just as the artists did in the 1960s and ’70s. Some have questioned whether or not it is appropriate to alter traditional music and combine it with modern elements.

For many, the resurgence and evolution of Cambodian rock music is a way of reclaiming what the Khmer Rouge tried to kill. By creating new music that blends traditional and modern influences, artists are shifting the narrative of Cambodian history from one of pain and suffering, to one of healing and resilience.

*Life years unknown. (Note that for many Cambodians who died under the Khmer Rouge regime, information about their death was often not recorded.)

Bibliography:

Lee, Erika. (2015). The Making of Asian America: A History. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Pirozzi, John. (Director). (2014). Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten: Cambodia’s Lost Rock and Roll [Film]. Argot Pictures.

Prak, Rane. (2022).

“Time to Rise”: Cultural Phenomenon in the Evolution of Cambodian Original Music. [Humanities Honors thesis]. The University of Texas at Austin.

http://dx.doi.org/10.26153/tsw/41924. Accessed 6 August 2024.

- Agrarian:relating to the cultivation of land

- Armed Forces Radio: a government television and radio broadcast service the U.S. military provides to those stationed or assigned overseas (now known as the American Forces Network)

- Colonial: relating to a colony, an area over which a foreign nation or state extends or maintains control

- Communism: a system in which goods are owned in common and are available to all as needed

- Cover: a recording or performance of a song previously recorded by another performer

- Curfew: a regulation requiring people to go home at a stated hour

- Disposable income: income that is left after paying taxes and for things that are essential, such as food and housing

- Dissident: person who disagrees, especially with an established religious or political system, organization, or belief

- Refugee: a person who flees to a foreign country or power to escape danger or persecution

- Resettle: to move to a new place to live after a disturbance or upheaval

- Patriotic: inspired by love for, or devotion to, one's country

- Propaganda: ideas, facts, or allegations spread deliberately to further one's cause or to damage an opposing cause

- Psychedelic: imitating, suggestive of, or reproducing effects (such as distorted or bizarre images or sounds) resembling those produced by psychedelic drugs

- Totalitarianism: the political concept that the citizen should be totally subject to an absolute state authority

- Trauma: a disordered psychic or behavioral state resulting from severe mental or emotional stress or physical injury

- What was the music scene like in Cambodia during the post-independence period (1953-1975)?

- What influenced the Cambodian rock scene of the 1960s and 1970s?

- Why did the Cambodian rock scene of the 1960s and 1970s come to an abrupt end?

- What was the Khmer Rouge’s perspective on music?

- How was Cambodian rock music introduced to the United States?

- How have younger generations of Cambodian Americans used music?

- What are some tensions around the rebirth of Cambodian rock in the United States?

Map of Cambodia showing major cities including the capital, Phnom Penh, as well as neighboring countries.

Credit: CIA The World Factbook (Public Domain Image)

Activity 1: Examining The Role of Music

- Have students write a Quickwrite in response to the prompt: “What role does music play in your life? What role does music play in society?” Provide an opportunity for students to share their responses.

- Have students locate Cambodia on a map (or use Google Maps) and share what they know about Cambodian history and Cambodian Americans.

- Tell students the following: “Cambodia is the English name of the country. The Khmer are the ethnic majority group native to Cambodia; they comprise over 95% of the Cambodian population. Khmer is also used to describe the official language of Cambodia. The terms Cambodian and Khmer can both be used to describe the people, culture, and history of Cambodia; that stated, individuals and communities may express a preference for how they want to be identified.”

- Tell students that this lesson is about Cambodian rock music, which was very popular in Cambodia in the 1960s and 1970s.

- Show the trailer for Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten: Cambodia's Lost Rock and Roll (2014) (Run time: 02:42). Have students share their thoughts, reactions, or questions about the trailer.

- Place the following quotes from the trailer around the room. Have students walk around the room and respond to the quotes using sticky notes.

- “There is a saying in Cambodia, ‘music is the soul of a nation.’”

- “This is so cool, it’s my generation. I was ready for more, and all of a sudden, it was all gone.”

- “The new Cambodia was going to be a revolutionary country, not contaminated by the West.”

- “I told them I was a banana seller. I was a singer. I lied to them. That saved my life.”

- “If you want to eliminate values of past societies, you have to eliminate the artists. Because artists are influential. Artists are close to the people.””

- Have students reconvene and share reflections on the quotes. Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- What connections did you make between the quotes/trailer and your response to the Quickwrite?

- Why is studying music and other cultural phenomena important in understanding history?

- What can learning about Cambodian rock music teach us that learning solely about socio-political events cannot?

- Implement activities (as needed, in order to build more prior knowledge) from The Asian American Education Project lesson entitled “Cambodian Refugees in the United States” and/or watch the video entitled, “Ugly History: The Khmer Rouge murders” for a brief history.

Sinn Sisamouth (left) and Ros Serey Sothea (right) were among Cambodia’s most popular musicians during the booming music scene in the 1960s-1970s.

Credit: Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Activity 2: Learning about the History of Cambodian Rock

- Have students read the essay. Consider the following options:

- OPTION 1: Have students read the essay independently either for homework or during class time.

- OPTION 2: Read aloud the essay and model annotating.

- OPTION 3: Have students read aloud in pairs or small groups.

- Facilitate a class discussion by asking students the Discussion Questions.

- Tell students that four broad categories can be used to understand how the unique circumstances of time and place shaped historical events and developments: economic, social, political, and cultural. Work with students to create shared definitions of each:

- Economic: related to trade, income, wealth, goods, services, etc.

- Social: related to society, social status, social mobility, etc.

- Political: related to the government, public affairs, laws, policies, etc.

- Cultural: related to ways of life, ideas, customs, traditions, social behavior, etc.

- Distribute the worksheet entitled, “Rise of Cambodian Rock.” Have students work in groups of four, and assign each student in the group one of the four categories (economic, social, political, or cultural). Have students use the essay and conduct additional internet research to find information about the economic, social, political, or cultural contexts in Cambodia from the period of independence in 1953, to the Fall of Phnom Penh in 1975.

- Have students record information about each category in the respective box.

- Have students share their findings with the group and take notes as their peers are sharing.

- Have groups use the information about all four categories to answer this question as a whole class: “How did economic, social, political, and cultural factors in Cambodia from 1953-1975 give rise to the Cambodian rock scene in the 1960s and 1970s?”

- Have students write a paragraph summarizing their responses at the bottom of the worksheet.

The band Dengue Fever performing at the Bluebird Theater in Denver, Colorado. Dengue Fever is an American band inspired by the Cambodian rock music of the 1960s-1970s.

Credit: “151 Dengue Fever (6763912797)” Photo by Jester Jay Goldman,

CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Activity 3: Examining the Rediscovery of Cambodian Rock in America

- Divide the class into four groups and assign each group to one of the following Cambodian American artists. Have students read the article about their assigned artist. (Encourage students to research the artist further, including listening to their music and/or watching a music video.)

- Laura Mam: “Across Languages And Generations, One Family Is Reviving Cambodian Original Music”

- Bochan Huy: “Cambodian-American Singer Fuses Khmer Classics with Oakland Beats”

- Chhom Nimol: “How this Cambodian American singer found her voice””

- Satica Nhem: “Satica on Pop Music's Inclusiveness Problem”

- Have students complete “Part 1: Artist’s Profile” of the worksheet entitled, “Cambodian American Musicians.”

- Have students write the artist’s name.

- Have students write a short biography of the artist.

- Have students summarize the artist’s reflections on the impact of Cambodian history, including the Khmer Rouge, on their music.

- Have students summarize the artist’s reflections on the impact or role of music in their lives.

- Have students write down 1-3 notable quotes from the artist.

- Have students complete “Part 2: Corroboration” of the worksheet. Tell students that corroboration is the ability to compare multiple pieces of information or sources in order to identify similarities and/or patterns, and that it is important to corroborate sources to draw reliable conclusions.

- Tell students that the articles they read feature interviews with the artists. Ask students, “Are interviews reliable? Why or why not?”

- Have a discussion about how interviews are reliable as accounts of a personal history, and how interviews are important because they can help readers understand how historical events impacted individuals and/or families.

- Have a discussion about the shortcomings of interviews, including the fact that they might include faulty memory, bias, etc.

- Have students write down sourcing information about the article they read by answering the following questions:

- Who wrote this article?

- When was it published?

- Where was it published?

- What is the purpose of the article?

- Have students corroborate the information in the article they read with the lesson essay by answering the following questions on the worksheet:

- What are points of corroboration between the article you read and the lesson essay? (What do the texts agree on?)

- What are points of contradiction between the article you read and the lesson essay? (What do the texts disagree on?)

- Have students form groups of four, with one student representing each of the Cambodian American artists. Have each student share about the artist they studied in these small groups. Have students discuss the following questions:

- What commonalities or themes did you identify amongst the four artists? What accounts for the commonalities?

- What differences did you identify amongst the four artists? What accounts for the differences?

- How is music a form of healing for these Cambodian American artists?

- How does music shape their identities as Cambodian Americans?

- Reconvene as a whole class. Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- How are contemporary Cambodian American artists shifting the narrative of Cambodian history from one of pain and suffering, to one of healing and resilience?

- How do the perspectives of these Cambodian American artists help us understand the past?

Activity 4: Defining the Legacy of Cambodian Rock

- Have students watch the music video entitled, “Sva Rom Monkiss - Laura Mam and The Like Me's” (2010). (Note: This is a cover of Pen Ran’s [also romanized as Pan Ron] “Sva Rom Monkiss” [“Monkey Dance”]. The exact date of this song is unknown, but Pen Ran was active ~1963-1975.)

- Have students write an interpretation of Laura Mam’s music video addressing the following prompts:

- What story is Mam telling in the music video?

- How does what you learned in this lesson help you make sense of the music video?

- How are the mother and daughter’s experiences shaped by historical and current events?

- Have students read Mam’s note/description below the video to better understand her intention with the song and video.

- Have students review their Quickwrite from Activity 1 on the role of music in their lives and in society. Have students write an essay addressing the prompt: “How does the history of Cambodian rock help people in the present understand Cambodian history? How does studying the role of rock music in Cambodian and Cambodian American society add additional dimensions to the study of history? What is the significance of contemporary Cambodian American artists like Laura Mam?”

- Secure the rights to screen Don't Think I've Forgotten: Cambodia's Lost Rock And Roll and facilitate a discussion by asking students the following questions: What was the impact of Cambodian rock music of the 1960s and 1970s on Cambodian musicians and their fans? Why were artists and musicians targeted by the Khmer Rouge? How does the film portray Cambodia? How does this portrayal shift common perspectives of Cambodia that focus on war and genocide?

- Have students research one of the artists mentioned in the lesson essay, or another Cambodian rock artist. Have students create biographies of the artists in the form of a poster, video, picture book, essay, comic, or social media post. Invite one of the contemporary Cambodian American artists as a guest speaker to your school site. (Have students raise funds to support the artist.)

D2.His.1.9-12.

Evaluate how historical events and developments were shaped by unique circumstances of time and place as well as broader historical contexts.

D2.His.7.9-12.

Explain how the perspectives of people in the present shape interpretations of the past.

D2.His.8.9-12.

Analyze how current interpretations of the past are limited by the extent to which available historical sources represent perspectives of people at the time.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.9-10.4

Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including vocabulary describing political, social, or economic aspects of history/social science.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.9-10.9

Compare and contrast treatments of the same topic in several primary and secondary sources.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.8

Evaluate an author's premises, claims, and evidence by corroborating or challenging them with other information.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.9

Integrate information from diverse sources, both primary and secondary, into a coherent understanding of an idea or event, noting discrepancies among sources.