1.3.0 - Chinese Massacre of 1871 –

Connecting the Past with the Present

Grades: 3-5Subjects:

English, Social Studies, U.S. HistoryNumber

of Activities: 4

The Massacre

Source: The Chinese American Museum

In this lesson, students will learn about the Los Angeles Chinatown Massacre of 1871. They will examine the attitudes and policies of the time which led to the Massacre. Students will learn about recent acts of anti-Asian violence and make connections between the Chinese Massacre and recent attacks.

Students will:

- Describe what happened during the Los Angeles Chinatown Massacre of 1871

- Identify the conditions, attitudes, and policies that led to anti-Chinese sentiments

- Make connections between the Chinese Massacre and recent acts of anti-Asian violence

This lesson and the videos include discussion of and materials discussing or depicting xenophobia, Sinophobia, and racial violence, including lynchings. Please let students know that this lesson will cover these topics and approach discussions with care. You may choose to modify and/or not to show them.

Chinese Massacre of 1871 Essay

Over 150 years ago, in 1870, there were 172 Chinese people in Los Angeles, a major city in California. At the time, white and other non-Chinese people saw the Chinese as

foreign. They believed the Chinese language, dress, traditions, and facial features were too different. They treated these immigrants like outsiders who did not belong in the United States. As a result, attacks against Chinese communities were often common.

The United States relied on Chinese workers. Chinese immigrants arrived in large groups from China starting in the 1850s. They helped build railroads and establish towns along the West Coast. The Chinese worked for less money than white workers. They also did jobs that white workers refused to do. More Chinese workers arrived in the United States. This worried many white workers who saw the Chinese immigrants as a threat. As the Chinese population increased,

xenophobia, specifically against Asians, also increased.

In 1870, more than half of Los Angeles’s Chinese population lived in the “Chinese

quarter.” This area was along a short street called Calle de Los Negros (later renamed Los Angeles Street). This street was named after the darker-skinned multiracial population who first lived there. Violence was common in this area.

On the afternoon of October 24, 1871, there was a shootout between two Chinese

tongs (groups) near Calle de Los Negros. A tong fighter was killed. Local police soon arrived at the scene. During the shootout, a white police officer was wounded, and Robert Thompson, a local white rancher and former saloonkeeper, was killed. Rumors started to spread. White city residents heard that Thompson was killed by Chinese fighters. This led to the formation of a mob of over 500 people. The mob tore through the Chinese

quarter. They targeted and attacked any Chinese person they saw. They attacked people that did not have any connection to the shootout earlier in the day. After three hours, eighteen Chinese people were killed, including a doctor and a fifteen-year-old boy. After the Massacre, five trials were held. Only ten of the five hundred rioters were charged with murder. Eight of them were sent to prison, but were released just a year later.

The 1871 Massacre was traumatic for the Chinese community of Los Angeles. They continued to suffer greatly from anti-Chinese attitudes and policies. They were denied rights. They weren’t allowed to own land or property. They also weren’t allowed to be citizens. They faced

discrimination and were attacked. The media continued to spread negative

stereotypes about the Chinese. This made the Chinese community vulnerable. However, the Chinese community refused to be turned aside. Within one year, more Chinese immigrants moved into the area. Some moved into the same buildings that were destroyed during the Massacre. The Chinese population of Los Angeles grew about five times more from 1870 to 1880. Chinese farmers on the outskirts of town became the main source of fresh food for Los Angeles. Chinese residents created successful businesses like grocery stores and restaurants. This thriving area became known as Chinatown.

The injustice of the 1871 Massacre did not go unanswered by the Chinese community. After the killings, some residents used the limited legal resources available to them to fight for

reparations for their losses. As of 2021, a

plaque embedded in the street of the old Chinese

quarter is the only reminder of the 1871 Massacre. Some believe more should be done to honor these victims who senselessly lost their lives.

Bibliography:

-

Discrimination: unfairly treating a person or group of people differently from other people or groups1

-

Foreign: outside a place or country1

-

Massacre: the killing of a large number of usually helpless or nonresistant human beings1

-

Naturalization: the admittance of a foreigner to the

citizenship of a country2

-

Plaque: a flat, thin piece of metal or wood with writing on it that is used especially as a reminder of something (such as a historic event or an achievement)3

- Reparation: the act of making amends or giving satisfaction for a wrong or injury1

-

Stereotype: a mental picture that represents a prejudiced or incomplete attitude or idea1

-

Tong: a hall or meeting place in Chinese; came to be used in the late 1800s by the white population to refer to the Chinese associations that provided other Chinese people with legal, monetary, and protective services and/or engaged in illegal activities3

-

Quarter: a division or district of a town or city1

-

Xenophobia: a hostility to, disdain for, or fear of foreigners, people from different cultures, or strangers2

- What led to the 1871 Massacre? What role did xenophobia play?

- After the Massacre, how did the Chinese community rebuild?

- Think about the anti-Chinese sentiment described in the essay. What similarities do you see today post-9/11 and during the COVID-19 pandemic? Draw on your personal experience, news stories, current events, books, social media, etc.

- What obstacles did the Chinese communities face, and still do?

Activity 1: Understanding the Chinese Massacre of 1871

This activity helps students identify the causes of the 1871 Massacre.

- Provide students opportunities to learn about the Chinese Massacre of 1871. Have students read or watch the following resources and provide scaffolding as needed:

- Read the Chinese Massacre of 1871 essay provided by the Asian American Education Project.

- Watch this lesson’s video, a clip from Buried History: Retracing the Chinese Massacre of 1871: https://vimeo.com/705445285 [Run time: 00:05:09]

- Watch a clip from Episode 1 of the PBS docuseries Asian Americans: https://vimeo.com/702393631 [Run time: 00:01:15]

- Have students work in small groups and have them write a list of what they learned from the resources they read and watched.

- Distribute the handout, “Chinese Massacre of 1871: Cause and Effect Organizer”. Have students use what they have learned to complete the chart. This can be done independently or in small groups. First, have students identify at least four causes of the Chinese Massacre of 1871 (complete the top half of handout). Second, have students describe what happened and who was harmed during the Chinese Massacre of 1871 (complete the bottom half of handout).

- Convene students as a whole group. Review the handout by discussing the causes of the Chinese Massacre of 1871 and what happened. Next, lead students in a discussion by asking: What were some of the effects or impacts of the Massacre? How are we still feeling the impacts today?

Description: Chinese New Year Parade Dragon

Credit: Chinese American Museum, Courtesy of Florence Ung Francis

Activity 2: Contextualizing the Chinese Massacre of 1871

This activity helps students understand the historical contexts of the Chinese Massacre of 1871 by creating a timeline.

- Have students work in small groups. Assign each small group to one of the following topics:

- California Gold Rush

- Ruling of “People v. Hall”

- Building of the Transcontinental Railroad

- Naturalization Act

- “Old Chinatown” in Los Angeles

- Chinese Exclusion Act

- Alien land laws

- “New Chinatown” in Los Angeles

- COVID-19 and Anti-Asian Hate

- Atlanta Spa Shooting

- Distribute the handout, “Chinese Massacre of 1871: Timeline Organizer”. As an example, model how to complete the chart by filling in the left column labeled “Chinese Massacre of 1871.” Identify the date, description, and connection or impact to Chinese immigrants. Draw a picture representing what happened.

- Have student groups research their assigned topic and complete the chart.

- Draw a line on the whiteboard or hang a string across the classroom. Have students place their organizers in chronological order on the line (or string).

- Have each group present their topic in chronological order. Responses should look like the following:

- California Gold Rush (1850s - Chinese immigrants arrived in the U.S. to search for gold.)

- Ruling of “People v. Hall” (1854 - This law denied the Chinese people the right to testify against white people in court.)

- Building of the Transcontinental Railroad (1863-1869 - Chinese laborers worked on the railroad, with some settling in the Los Angeles area.)

- Naturalization Act (1870 - This law extended naturalization rights to aliens of African descent but imposed bans for other racial groups, specifically Asians.)

- “Old Chinatown” (1880s -1910 - The first L.A. Chinatown that thrived after the Massacre.)

- Chinese Exclusion Act (1882 - This law banned Chinese workers from immigrating to the U.S.)

- Alien land laws (1913 - These laws denied Asians the right to own land or property.)

- “New Chinatown” (1938 - Old Chinatown was razed to make way for train stations and highways, with New Chinatown developing in downtown Los Angeles.)

- COVID-19 and Anti-Asian Hate (2020 - As a result of referring to COVID-19 as the “China Virus” and “Kung Flu,” Asian Americans suffered from a rise in anti-Asian hate during the pandemic.)

- Atlanta Spa Shooting (2021 - Six Asian American women were killed in their place of work.)

- Convene students as a whole group and facilitate a discussion with the following prompts: What similarities and differences do you notice between all the topics? In what ways does anti-Asian hate present itself in each topic?

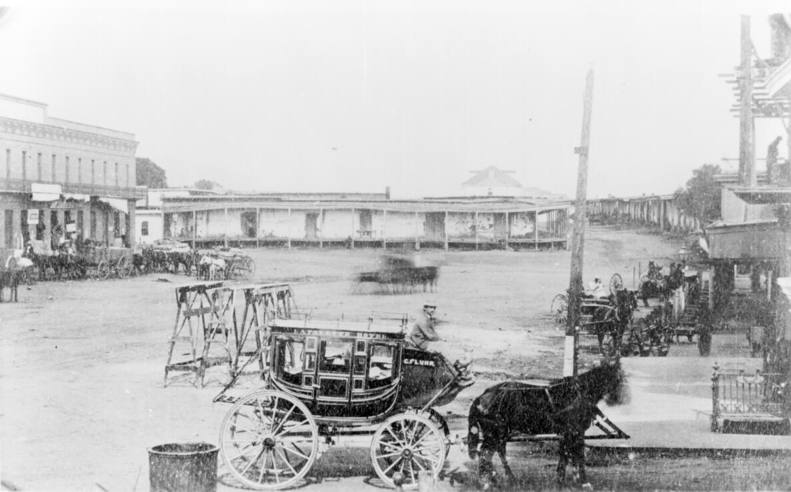

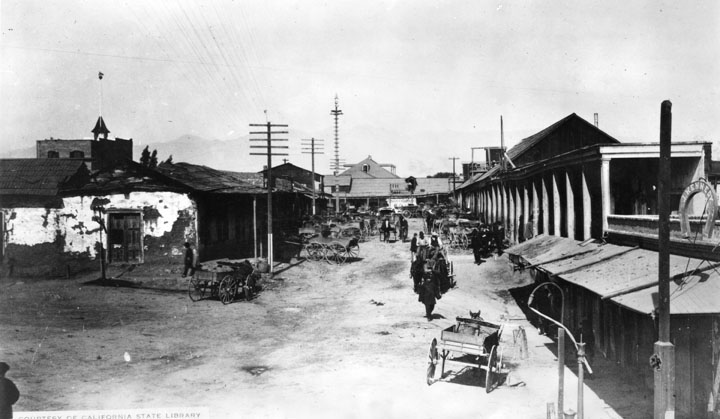

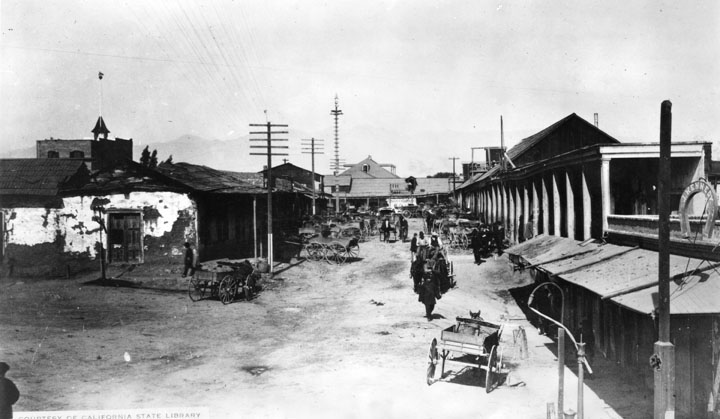

Description: L.A. Chinatown, circa 1880: Calle de los Negros on the right and the Coronel Adobe, white building, on the left. This is the site where the Chinese Massacre of 1871 began.

Credit: University of Southern California Libraries & California Historical Society, digitally reproduced by USC Digital Library

Activity 3: Connecting the Chinese Massacre of 1871 to Today

This activity helps students connect the Chinese Massacre of 1871 to the anti-Asian hate happening today.

- Watch the CNBC video, “Remembering the Chinese Massacre of 1871”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m7-xpchI6zM (Run time: 2 min. 31 sec.)

- Facilitate a discussion given these prompts:

- What is the connection of the 1871 Massacre to today’s anti-Asian hate?

- How are people working to combat anti-Asian hate?

- Watch the San Francisco Chronicle video, “Anti-Asian Violence Has Long History and Must Be Addressed”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vy4p-btsoX (Run time: 3 min. 14 sec.)

- Facilitate a discussion given these prompts:

- What is the main claim being presented in the video?

- What are the causes of today’s wave of anti-Asian hate? How are these causes an extension of the violence that occurred during the Chinese Massacre of 1871?

- Why do words matter? What roles does the media play in spreading negative messages?

- Have students write a personal response to the following prompt: Describe a time someone was mean to you for no reason. What happened? How did you feel? What did you do about it?

- Facilitate a whole group discussion with the following prompts:

- How does learning about the Chinese Massacre of 1871 help prevent future violence?

- What are the similarities and differences between the Chinese Massacre of 1871 and the current escalation of anti-Asian hate during the COVID-19 pandemic?

- Why is it important to know that anti-Asian hate is a part of U.S. history?

Description: Commemoration Wreath at Chinese American Museum, 2021 at the 150th Anniversary of the Chinese Massacre of 1871

Credit: Chinese American Museum

Extension Activity: Commemorating through Museums

This activity helps students build and demonstrate a deeper understanding of the Chinese Massacre of 1871 in a creative way.

- Explain how museums can be used as a form of reparations by serving as a space for education and awareness, preservation, and justice.

- Reparations means fixing something that was wrong. For example, reparations for stealing someone’s pencil could be to return the pencil, giving that person a new pencil, giving that person enough money to buy their own pencil, and more.

- Ask students: when thinking about the Chinese Massacre of 1871, what about the massacre would require reparations?

- If missing in students’ answers, share that different types or reasons for reparations could include: for the massacre itself (the lives lost, property destroyed, other stolen money and items), for the way Chinese people were treated and the ways laws discriminated against Chinese people in the U.S., and for the lack of knowledge or recognition of the massacre.

- Give students the following scenario: The City of Los Angeles is creating a museum exhibit to recognize the Chinese Massacre of 1871.

- Have students design a museum exhibit. The exhibit should include the following:

- Title: The name of your exhibit. It should present the main point of your exhibit to visitors.

- Description: The text found at the beginning of the exhibit. It should provide some history and background information related to the exhibit.

- Items: The photographs, art, items, etc. that make up the exhibit and are what people have come to see. Make sure to include where you found each item. (Example: For a photograph, who took it and/or where did it come from?)

- Provide students with the images in the Chinese Massacre Museum Activity Historical Images as a starting point.

- Layout: This is where the title, description, and each item go in your room. You can decide the shape and size of the museum but make sure the order of the information you’re sharing makes sense and is easy for the visitor to follow.

- Have students create a visual representation of their exhibit in the form of a poster. Display all the finished products around the classroom and have students do a gallery walk to look at each other’s work.

- Have students complete a quickwrite on what they learned and noticed in each other’s work.

- This video clip provides background on Los Angeles and Chinese Americans in the late 1800s. It includes an animated depiction of the massacre, which may not be suitable for younger audiences.

- Students can study this 1871 political cartoon and consider its connection to the Chinese Massacre of 1871.

- This video clip can be used to provide another recounting of the event, and also contains photographs which can be studied as primary documents.

Woo, Elaine (Producer) & LeeWong, Cameron (Director). October 2021.

Buried History: Retracing the Chinese Massacre of 1871 [Motion picture]. United States: Chinese American Museum.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hjZmMUZgwrQ. Accessed 05 May 2022

- This is the full film and includes a full, detailed account of the massacre, as well as descriptions of parts of the massacre that may not be suitable for younger audiences.

California Common Core Standards Addressed

Common Core ELA Anchor Standards for Reading:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.1

Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.2

Determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their development; summarize the key supporting details and ideas.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.8

Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, including the validity of the reasoning as well as the relevance and sufficiency of the evidence.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.9

Analyze how two or more texts address similar themes or topics in order to build knowledge or to compare the approaches the authors take.

Common Core ELA Anchor Standards for Writing:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.W.7

Conduct short as well as more sustained research projects based on focused questions, demonstrating understanding of the subject under investigation.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.W.9

Draw evidence from literary or informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.W.10

Write routinely over extended time frames (time for research, reflection, and revision) and shorter time frames (a single sitting or a day or two) for a range of tasks, purposes, and audiences.

Common Core ELA Anchor Standards for Speaking and Listening:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.SL.1

Prepare for and participate effectively in a range of conversations and collaborations with diverse partners, building on others' ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.SL.2

Integrate and evaluate information presented in diverse media and formats, including visually, quantitatively, and orally.

Social Justice Standards (The Learning for Justice Anti-Bias Framework):

Diversity 8

Students will respectfully express curiosity about the history and lived experiences of others and will exchange ideas and beliefs in an open-minded way.

Diversity 10

Students will examine diversity in social, cultural, political and historical contexts rather than in ways that are superficial or oversimplified.

Justice 12

Students will recognize unfairness on the individual level (e.g., biased speech) and injustice at the institutional or systemic level (e.g., discrimination).

Justice 13

Students will analyze the harmful impact of bias and injustice on the world, historically and today.