Grades: 6-12Subjects:

English, Social Studies, U.S. HistoryNumber

of Activities: 4

A mob of 500 people (10% of the population of Los Angeles at the time of the massacre) attacked Chinatown

Source: Buried History: Retracing the Chinese Massacre of 1871

In this lesson, students will learn about the Los Angeles Chinese Massacre of 1871, and identify the causes by examining the attitudes and policies of the time. They will learn about and analyze other massacres that have occurred in the United States in order to gain a better and more nuanced understanding of how and why these acts of violence occur. Lastly, students will research the process for reparations and consider how to address and rectify the harm of such injustices.

Students will:

- Describe what happened during the Chinese Massacre of 1871

- Identify the causes and effects of the Chinese Massacre of 1871

- Identify the conditions, attitudes, and policies that led to anti-Chinese sentiments

- Compare the 1871 Massacre to other instances of racist and xenophobic violence in the U.S.

- Examine processes for reparations and community healing

This lesson includes discussion of and materials discussing or depicting xenophobia, Sinophobia, and racial violence, including lynchings. Please let students know that this lesson will cover these topics and approach discussions with care.

Chinese Massacre of 1871 Essay

In 1870, according to the U.S. Census, the Chinese population of Los Angeles was 172 people—about 3% of the city’s population. Although Chinese immigrants accounted for only 10% of California’s total population, they made up 25% of the workforce. Many businesses and households relied on Chinese labor, but these immigrants were exploited on the job and denied access to rights—victims of

yellow peril. As such, the Chinese were seen as foreign,

unassimilable, and a threat to white workers.

Random anti-Chinese attacks were not uncommon at the time. Additionally, between 1868 and 1870, the Ku Klux Klan led more than a dozen organized attacks on Chinese people in the state of California alone. As the Chinese population grew, becoming more visible in the state (and across the country),

Sinophobia increased dramatically; and this anti-Asian sentiment was aided and exacerbated by the racist policies and attitudes of those with power. In 1870, the U.S. Congress passed the

Naturalization Act, which extended naturalization rights to aliens of African descent but imposed naturalization bans for other racial groups, specifically Asians.

In 1870, more than half of Los Angeles’s Chinese population lived in the “Chinese quarter” along Calle de Los Negros (later renamed Los Angeles Street), a short street named after the darker-skinned multiracial population who originally lived there. When the original residents moved out, Calle de Los Negros became a

vice district where violence was often common. Frustrated Angelenos faulted the legal system for failing to protect their neighborhoods; as such, they formed a committee of

vigilantes who meted out punishment against accused criminals. Starting in 1848, Los Angeles received an influx of new city residents, including failed gold miners from the north, soldiers from disbanded regiments, outlaws, and more; with Chinese immigrants among these new residents. Over the next two decades, Calle de Los Negros became more violent, as disputes were frequently settled with guns. Additionally, as the white community sought to consolidate its power, Calle de Los Negros became the scene of many acts of violence against non-white people, especially Mexican and Chinese residents.

The earliest Chinese in Los Angeles, like others, also settled their disputes with guns. After a series of smaller confrontations earlier in 1871, a larger shootout began on the afternoon of October 24th between two

tongs (factions) near Calle de Los Negros. A tong fighter was killed, and local police soon arrived at the scene. In the crossfire of the shootout, a white police officer was wounded, and Robert Thompson, a local white rancher and former saloonkeeper, was killed. There was a cry to take revenge against the Chinese. A mob of around five hundred rampaged through the Chinese quarter, targeting and assaulting any Chinese person they saw, regardless of whether they had any connection to the shootout. After about three hours, eighteen Chinese people were killed—with three shot to death and fifteen hung—including a prominent local doctor, Dr. Tong, and a fifteen-year-old boy. In the following months, a grand jury was convened and five trials were held. Eventually, ten of five hundred rioters were charged with the murder of Dr. Tong; eight were found guilty of

manslaughter and sent to San Quentin prison, but all were released a year later when their sentences were overturned on a

technicality.

While the 1871

Massacre was a traumatic and devastating event for the Chinese community of Los Angeles, it did not stop the growth of their community. Within a year, more Chinese immigrants moved into the area; some into the very buildings that were targeted and destroyed by the mob. The city’s Chinese population multiplied five-fold over the next decade. By the 1890s, much of the Chinese population and business establishments had moved to an area to the north, on both sides of Alameda Street—and became known as Chinatown. Chinese farmers on the outskirts of town became the dominant source of fresh fruits and produce for Los Angeles, and Chinatown became a commercial hub as new grocery stores, restaurants, and labor contractors prospered. This success came about despite ongoing political and social obstacles, such as the Chinese Exclusion Act, alien land laws, and other challenges to social integration.

However, the negative media messages against the Chinese and Chinatown made the community vulnerable to exploitation. For example, the City of L.A and local railroad companies wanted to build a central rail passenger terminal, and Chinatown was located in a prime spot for it. Investors and the Southern Pacific Transportation Company started acquiring land in Chinatown, and by the early 1930s

evictions began. The eastern half of Chinatown was then razed to make way for Union Station, and the rest of the neighborhood was demolished by the State of California for the 101 Freeway, displacing 3,000 Chinese residents. Even though the

evictions took place decades after the Massacre, Chinese Angelenos were, and are, still seen as foreigners and outsiders.

Throughout this country’s history, there have been many other massacres also similarly motivated by racism and

xenophobia. These include, but are not limited to, the following: (1) the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre at Pine Ridge Reservation where around 300 Native Americans were killed; (2) the 1919 Elaine Massacre of 200-800 Black men, women, and children; and (3) the 2012 Oak Creek Massacre that targeted a Sikh

gurdwara, killing six and wounding four people. These are just a few examples of the

genocides, massacres, and ethnic, racial, and class violence against communities of color that are a part of America’s social and racial history.

It is also necessary to acknowledge that these injustices do not occur without actions or responses from the affected communities. At the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre, some of the Lakota present fought back against the U.S. soldiers, saving the lives of others by giving them a chance to escape. Following the Elaine Massacre in 1919, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and Ida B. Wells, a prominent journalist and anti-

lynching activist, conducted their own investigations and produced writings that resisted and refuted the white

perpetrators’ account that the massacre had occurred in response to a supposed insurrection being planned by the Black residents of Elaine. In 2012 in Oak Creek, the son of one of the victims started an organization that aims to promote a healthy sense of identity, purpose, and belonging among young people. Another Oak Creek resident organized an annual anniversary event that grieves for those lost and raises money for a scholarship fund in memory of the victims. Following the Chinese Massacre of 1871, some of the affected Chinese residents utilized the limited legal avenues available to them to try to obtain

reparations for their losses.

These communities of color found ways to fight back, survive, grieve, heal, and protest in the face of injustices. However, to create a safe and healthy society that values all individuals, regardless of their race, class, religion or other characteristics, the personal, societal and institutional tensions that led to such massacres must be addressed and reconciled. As of 2021, the 1871 Massacre in the old Chinese quarter is commemorated solely by a plaque embedded in the pavement on Los Angeles Street.

Bibliography:

-

Eviction: the forced removal of someone from a place, often by using a legal process1

-

Genocide: the deliberate and systematic destruction of a group of people because of their ethnicity, nationality, religion, or race2

-

Gurdwara: a place of worship for Sikhs2

-

Lynching: to put to death, especially by hanging, by mob action and without legal authority2

-

Manslaughter: an action in which a person’s death occurs, but is not the intention of the action; different from “murder,” which is defined as an action that is intended to result in a person’s death3

-

Massacre: the killing of a large number of usually helpless or non-resisting human beings4

-

Naturalization: process by which a foreign citizen becomes a citizen of a new country5

-

Perpetrator: someone who committed a crime, or a violent or harmful act 1

-

Reparation: the act of making amends; something done or given as amends, such as a payment for damages4

-

Sinophobia: a fear or dislike of China, or Chinese people, their language or culture6

-

Technicality: in legal terms, a point that is based on a strict interpretation of the law or a set of rules6

-

Tong: a hall or meeting place; came to be used by the white population in the late 1800s to refer to Chinese associations that provided Chinese people with legal, monetary, and protective services and/or engaged in illegal activities2

-

Unassimilable: unable to be absorbed or integrated into a wider society or way of thought7

-

Vice: illegal and immoral activities, especially involving sex, drugs, etc.5

-

Vigilante: a member of a volunteer committee organized to suppress and punish crime; any person who takes the law into their own hands4

-

Xenophobia: a hostility to, disdain for, or fear of foreigners, people from different cultures, or strangers1

-

Yellow Peril: the perceived threat to Western living standards from the influx of eastern Asian laborers willing to work for very low wages4

Exterior View of the Pekin Curio Store in Los Angeles Plaza, ca.1909

Source:

Wikimedia Commons

- What are some causes of the anti-Chinese sentiments that led to the 1871 Massacre?

- Why is it important to recognize that the Chinese Massacre of 1871 was not an isolated incident?

- How was the 1871 Massacre commemorated? Why should it be commemorated? In general, how should traumatic and deadly events, like massacres, be commemorated?

- Why is it important to recognize how communities of color responded to race-based violence? Why is it essential for these communities to be seen as more than just victims?

- How can we, as a society, prevent and/or respond to race-based violence in order to create safer, healthier, and happier communities?

Joss House in Chinatown

Credit: Chinese American Museum, Courtesy of the Southwest Museum of Los Angeles

Activity 1: Understanding the History of Anti-Asian Violence

This activity aims to contextualize and discuss the many causes of the 1871 Massacre.

- Have students read the Chinese Massacre of 1871 essay provided by the Asian American Education Project.

- Provide additional context of how Chinese people in the United States were treated by playing this clip from Episode 1 of the PBS docuseries Asian Americans: https://vimeo.com/702393631 [Run time: 00:01:15].

- Have students discuss the causes and effects of the propaganda around the rallying cry, “The Chinese Must Go.”

- Have students watch a clip from Buried History: Retracing the Chinese Massacre of 1871: https://vimeo.com/707529291[Run time: 00:07:18]

- Have students read Kevin Waite’s article, “The Bloody History of Anti-Asian Violence in the West”.

- If needed, provide scaffolding by assisting students in a close reading of the texts. For example, have students annotate the text by marking details and examples that help them determine the causes and effects of anti-Asian violence.

- Convene students as a whole group and facilitate a discussion on the following prompts:

- What did you learn from the texts? What are the main claims? Do you agree or disagree with the claims?

- Who participated in the Massacre and what were their roles in providing fuel for the Massacre?

- What policies, attitudes, etc., caused or contributed to Sinophobia?

- Distribute the handout titled, “Chinese Massacre Cause and Effect Organizer.” Have students use what they have learned from the video clips and texts to complete the chart.

- First, have students identify at least four causes of the Chinese Massacre of 1871 (on top half of the handout).

- Second, have students describe what happened and who was harmed during the Chinese Massacre of 1871 (on bottom half of the handout).

- Convene the students as a whole group. Review the handout by discussing the causes of the Chinese Massacre of 1871 and what happened. Next, lead a discussion using the following prompts:

- What are the similarities and differences between the Chinese Massacre of 1871 and the current escalation of anti-Asian hate during the COVID-19 pandemic? If students need more context about current anti-Asian hate, review several recent news articles, including reports and data from Stop AAPI Hate.

- What are the causes of current anti-Asian violence? How are these causes an extension of the violence that occurred in the Chinese Massacre of 1871?

- Why is it important to know that anti-Asian hate is a part of U.S. history?

Chinese Dragon Procession

Credit: Chinese American Museum, Courtesy of Florence Ung Francis

Activity 2: Contextualizing the Chinese Massacre of 1871

This activity aims to compare the 1871 Massacre to other acts of xenophobic and racist violence in the U.S.

- Explain to students that there have been many examples of race-based hate in the United States. As a whole group, lead students through a brainstorming session and ask them to give examples of race-based hate in the U.S. Record student responses.

- Distribute the handout titled, “Chinese Massacre Comparison Research Organizer.” As a whole group, complete the first column under “Chinese Massacre of 1871.” Demonstrate how to complete the organizer by asking the following questions as you complete the chart:

- Location & Date: Where and when did this event take place?

- Targeted Group: Who was victimized?

- Target Group’s History: What is the history of the victimized group, locally and around the country? Were they recent immigrants, part of a segregated community, members of a minority religious group, organizing against racist laws, etc.?

- Prevailing Perceptions of Targeted Group: How was the targeted group perceived at the time? What stereotypes did they face?

- Documented Harm: What was the physical impact/damage of the violence? Consider the number of people killed, injured, and other damages to the community, including property damage, etc.

- Perpetrator(s): Who were the attackers?

- Causes: Why did the perpetrators attack the targeted group? What caused this event to take place?

- Impacts: What were some immediate and long-term effects of the event? Consider how the impacted community, lawmakers, media, etc., reacted to the event.

- Organize students into groups of 2-3. Assign each group to one of the below topics (feel free to add examples from the brainstorming session—make sure the topics address different ethnic groups):

- Rock Springs Massacre (1885)

- Wounded Knee Massacre at Pine Ridge Reservation (1890)

- Porvenir Massacre (1918)

- Elaine Massacre (1919)

- Tulsa Race Massacre (1921)

- Oak Creek Massacre (2012)

- Have groups research and complete the organizer. Have students discuss how their assigned event is similar to and different from the Chinese Massacre of 1871. Have students create a visual of the content they learned about and present it to the class.

- Convene students as a whole group and discuss the following prompts:

- How are these events similar to and different from the Chinese Massacre of 1871?

- What are some common themes, consequences, causes, etc., across all these race-based hate events?

- Some of these events, like the Chinese Massacre of 1871, are relatively unknown to the wider public. Why might this be the case?

- How are these events examples of racism and systemic oppression?

- White supremacy is a root cause of these race-based hate events. Knowing this, what can be done to diminish white supremacy?

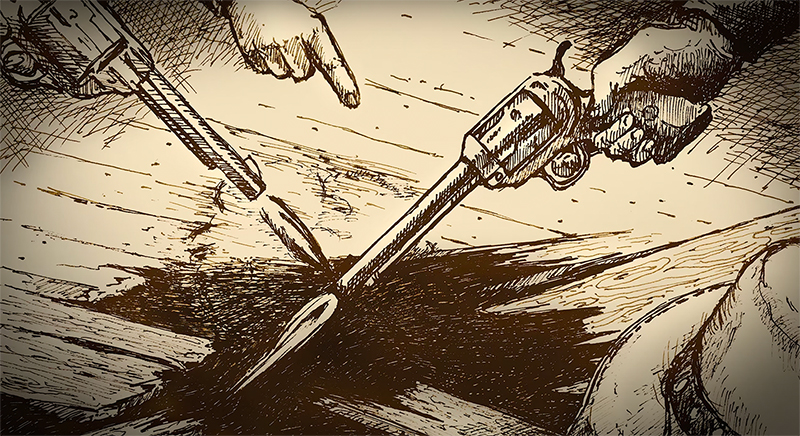

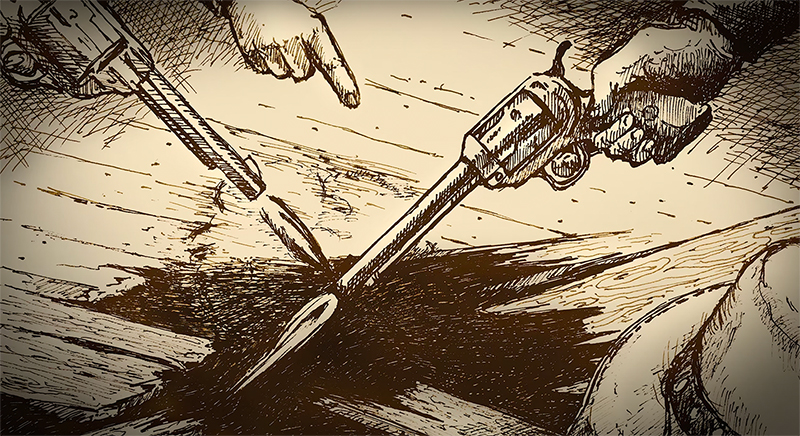

Shooting through the roof. Killing innocent Chinese.

Source: Buried History: Retracing the Chinese Massacre of 1871

Activity 3: Truth & Reconciliation

This activity helps students consider how an injustice as deeply impactful and harmful as a massacre can be reconciled and how the impacted community might be able to find justice and healing.

- Explain to students: Truth and reconciliation processes are used to publicly discuss, establish, and understand the scale of harm and impact of a past injustice. This includes hearing from people who had committed harm, experienced harm, witnessed harm, and who were otherwise involved in or affected by the injustice. This process not only makes the injustice a part of the public record, keeping it from being erased or forgotten, but also often outlines how that harm can be addressed and rectified.

- Have students read the Los Angeles Public Library’s blog, “Forgotten Los Angeles History: The Chinese Massacre of 1871.” Have students write a personal response (i.e., quickwrite) to the last paragraph: “The tragedy was quickly forgotten: the local newspapers made no mention of it in the year end recap of major events of the year. The unfortunate truth is that little changed in Los Angeles as a result of the massacre of October 24. The massacre did not result in racial tolerance, in fact, anti-Chinese sentiment increased in the following years. The Anti-Coolie club was formed in 1876, counting many prominent citizens among its members, and the newspapers resumed their editorial attacks against the Chinese.”

- Have students read Kevin Waite’s Los Angeles Times Op-Ed, “Start atoning for past racism, L.A. – build a memorial to victims of the Chinese Massacre.” As a whole group, have students identify the claim and arguments/examples Waite uses to support his claim. Have students write a personal response (i.e., quickwrite) to the following prompt: To what extent do you agree or disagree with Waite?

- Distribute the handout titled, “Chinese Massacre Truth and Reconciliation Organizer.” Have students research at least two truth and reconciliation processes that have already happened. Have students identify the targeted group(s); perpetrator(s); summary of what happened, group(s) seeking truth and reconciliation; this group’s objective(s); this group’s process; and the outcome to date. Students may pick from, but not limited to, the following list:

- Greensboro Truth and Reconciliation Commission for the Greensboro Massacre

- Truth Commission for Tulsa Race Massacre

- Maine Wabanaki-State Truth and Reconciliation Commission for Maine Child Welfare System

- National Commission of the Disappearance of Persons (Argentina)

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission for Canadian Indian Residential School System

- National Truth and Reconciliation Commission for Augusto Pinochet Regime (Chile)

- Truth and Justice Commission for Impact of Slavery and Indentured Servitude (Mauritius)

- Panama Truth Commission for Military Rule of Omar Torrijos and Manuel Noriega

- Truth and Reconciliation Process for Apartheid (South Africa)

- Convene as a whole group and discuss the following prompts:

- Consider the truth and reconciliation processes you researched. How do the outcomes or recommendations of those processes relate to the creation of a harm-free society?

- Should there be a truth and reconciliation process for the Chinese Massacre of 1871?

- Based on historical examples, what is a process that could be used to discuss and rectify the harm that was caused by the 1871 massacre? Who must be included in this process, and what are their roles?

- How do we create a society and culture in which it would be unthinkable to harm, let alone kill, someone else? What challenges would we need to overcome and what currently stands in the way of this happening?

- Have students create a public comment pitch (consisting of two minutes of speaking) addressed to the City of Los Angeles (or State of California) about what type of truth and reconciliation process should be used, and the intended outcome should be. Direct students to give a brief background on the Massacre and how a truth and reconciliation process would be beneficial.

Candlelight Vigil at Chinese American Museum, 2021

Credit: Chinese American Museum

Activity 4: Commemorating through Museums

This activity helps students build a deeper understanding of the Chinese Massacre of 1871 in a creative way.

- Explain how museums can be used as a form of reparations by serving as a space for education and awareness, preservation, and restorative justice.

- Give students the following scenario: The City of Los Angeles has agreed to create a museum exhibit commemorating the Chinese Massacre of 1871.

- Have students design a museum exhibit. The exhibit should include the following:

- Title: The name of your exhibit. It should communicate the theme to museum visitors.

- Description: The text found at the beginning of the exhibit. It provides some context and background information.

- Items: The artifacts that showcase the exhibit. This can include photographs, art, diagrams, tableau scenes, etc. Make sure to give credit to the source of the item whenever applicable.

- Ask students to research for artifacts on the Internet or in libraries.

- You may show students these resources as starting points for gathering images for their exhibit: “Chinese Massacre of 1871 – Historical Images” and https://wikimili.com/en/Chinese_massacre_of_1871

- Layout: This includes the room size/shape, placement and flow of information, stylistic elements (such as font types, colors, sizes, etc.), use of other multimedia elements, etc.

- Have students create a visual representation of their exhibit via a slide deck, posters, etc. Display all the finished products around the classroom and have students do a gallery walk to look at each other’s work.

- Have students complete a quickwrite reflecting on what they learned and noticed in each other’s work.

“The Jade Pendant.” Directed by Po-Chih Leong, Lotus Entertainment. 2017.

Woo, Elaine (Producer) & LeeWong, Cameron (Director). October 2021.

Buried History: Retracing the Chinese Massacre of 1871 [Motion picture]. United States: Chinese American Museum.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hjZmMUZgwrQ. Accessed 05 May 2022

California Common Core Standards Addressed

Social Justice Standards (The Learning for Justice Anti-Bias Framework):

Diversity 8

Students will respectfully express curiosity about the history and lived experiences of others and will exchange ideas and beliefs in an open-minded way.

Diversity 10

Students will examine diversity in social, cultural, political and historical contexts rather than in ways that are superficial or oversimplified.

Justice 12

Students will recognize unfairness on the individual level (e.g., biased speech) and injustice at the institutional or systemic level (e.g., discrimination).

Justice 13

Students will analyze the harmful impact of bias and injustice on the world, historically and today.

College- and Career-Readiness Anchor Standards:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.1

Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.2

Determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their development; summarize the key supporting details and ideas.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.7

Integrate and evaluate content presented in diverse media and formats, including visually and quantitatively, as well as in words.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.8

Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, including the validity of the reasoning as well as the relevance and sufficiency of the evidence.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.4

Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.W.7

Conduct short as well as more sustained research projects based on focused questions, demonstrating understanding of the subject under investigation.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.9

Draw evidence from literary or informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.9

Draw evidence from literary or informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.SL.1

Prepare for and participate effectively in a range of conversations and collaborations with diverse partners, building on others' ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.SL.2

Integrate and evaluate information presented in diverse media and formats, including visually, quantitatively, and orally.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.L.1

Demonstrate command of the conventions of standard English grammar and usage when writing or speaking.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.L.4

Determine or clarify the meaning of unknown and multiple-meaning words and phrases by using context clues, analyzing meaningful word parts, and consulting general and specialized reference materials, as appropriate.

Grade 6:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.6.1

Cite textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.6.2

Determine a central idea of a text and how it is conveyed through particular details; provide a summary of the text distinct from personal opinions or judgments.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.6.7

Integrate information presented in different media or formats (e.g., visually, quantitatively) as well as in words to develop a coherent understanding of a topic or issue.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.6.8

Trace and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, distinguishing claims that are supported by reasons and evidence from claims that are not.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.6.4

Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.6.7

Conduct short research projects to answer a question, drawing on several sources and refocusing the inquiry when appropriate.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.6.9

Draw evidence from literary or informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.6.1

Engage effectively in a range of collaborative discussions (one-on-one, in groups, and teacher-led) with diverse partners on grade 6 topics, texts, and issues, building on others' ideas and expressing their own clearly.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.6.2

Interpret information presented in diverse media and formats (e.g., visually, quantitatively, orally) and explain how it contributes to a topic, text, or issue under study.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.6.4

Present claims and findings, sequencing ideas logically and using pertinent descriptions, facts, and details to accentuate main ideas or themes; use appropriate eye contact, adequate volume, and clear pronunciation.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.L.6.1

Demonstrate command of the conventions of standard English grammar and usage when writing or speaking.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.L.6.4.A

Use context (e.g., the overall meaning of a sentence or paragraph; a word's position or function in a sentence) as a clue to the meaning of a word or phrase.

Grade 7:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.7.1

Cite several pieces of textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.7.2

Determine two or more central ideas in a text and analyze their development over the course of the text; provide an objective summary of the text.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.7.8

Trace and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, assessing whether the reasoning is sound and the evidence is relevant and sufficient to support the claims.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.7.4

Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.7.7

Conduct short research projects to answer a question, drawing on several sources and generating additional related, focused questions for further research and investigation.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.7.9

Draw evidence from literary or informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.7.1

Engage effectively in a range of collaborative discussions (one-on-one, in groups, and teacher-led) with diverse partners on grade 7 topics, texts, and issues, building on others' ideas and expressing their own clearly.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.7.2

Analyze the main ideas and supporting details presented in diverse media and formats (e.g., visually, quantitatively, orally) and explain how the ideas clarify a topic, text, or issue under study.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.7.4

Present claims and findings, emphasizing salient points in a focused, coherent manner with pertinent descriptions, facts, details, and examples; use appropriate eye contact, adequate volume, and clear pronunciation.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.L.7.1

Demonstrate command of the conventions of standard English grammar and usage when writing or speaking.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.L.7.4.A

Use context (e.g., the overall meaning of a sentence or paragraph; a word's position or function in a sentence) as a clue to the meaning of a word or phrase.

Grade 8:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.7.1

Cite several pieces of textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.8.1

Cite the textual evidence that most strongly supports an analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.8.2

Determine a central idea of a text and analyze its development over the course of the text, including its relationship to supporting ideas; provide an objective summary of the text.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.8.8

Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, assessing whether the reasoning is sound and the evidence is relevant and sufficient; recognize when irrelevant evidence is introduced.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.8.4

Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.8.7

Conduct short research projects to answer a question (including a self-generated question), drawing on several sources and generating additional related, focused questions that allow for multiple avenues of exploration.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.8.9

Draw evidence from literary or informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.8.1

Engage effectively in a range of collaborative discussions (one-on-one, in groups, and teacher-led) with diverse partners on grade 8 topics, texts, and issues, building on others' ideas and expressing their own clearly.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.8.2

Analyze the purpose of information presented in diverse media and formats (e.g., visually, quantitatively, orally) and evaluate the motives (e.g., social, commercial, political) behind its presentation.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.8.4

Present claims and findings, emphasizing salient points in a focused, coherent manner with relevant evidence, sound valid reasoning, and well-chosen details; use appropriate eye contact, adequate volume, and clear pronunciation.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.L.8.1

Demonstrate command of the conventions of standard English grammar and usage when writing or speaking.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.L.8.4.A

Use context (e.g., the overall meaning of a sentence or paragraph; a word's position or function in a sentence) as a clue to the meaning of a word or phrase.

Grade 9-10:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.9-10.1

Cite strong and thorough textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.9-10.2

Determine a central idea of a text and analyze its development over the course of the text, including how it emerges and is shaped and refined by specific details; provide an objective summary of the text.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.9-10.3

Analyze how the author unfolds an analysis or series of ideas or events, including the order in which the points are made, how they are introduced and developed, and the connections that are drawn between them.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.9-10.7

Analyze various accounts of a subject told in different mediums (e.g., a person's life story in print and multimedia), determining which details are emphasized in each account.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.9-10.8

Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, assessing whether the reasoning is valid and the evidence is relevant and sufficient; identify false statements and fallacious reasoning.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.9-10.4

Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.9-10.7

Conduct short as well as more sustained research projects to answer a question (including a self-generated question) or solve a problem; narrow or broaden the inquiry when appropriate; synthesize multiple sources on the subject, demonstrating understanding of the subject under investigation.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.9-10.9

Draw evidence from literary or informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.9-10.1

Initiate and participate effectively in a range of collaborative discussions (one-on-one, in groups, and teacher-led) with diverse partners on grades 9-10 topics, texts, and issues, building on others' ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.9-10.2

Integrate multiple sources of information presented in diverse media or formats (e.g., visually, quantitatively, orally) evaluating the credibility and accuracy of each source.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.9-10.4

Present information, findings, and supporting evidence clearly, concisely, and logically such that listeners can follow the line of reasoning and the organization, development, substance, and style are appropriate to purpose, audience, and task.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.L.9-10.1

Demonstrate command of the conventions of standard English grammar and usage when writing or speaking.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.L.9-10.4.A

Use context (e.g., the overall meaning of a sentence, paragraph, or text; a word's position or function in a sentence) as a clue to the meaning of a word or phrase.

Grade 9-10:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.9-10.1

Cite strong and thorough textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.11-12.1

Cite strong and thorough textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text, including determining where the text leaves matters uncertain.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.11-12.2

Determine two or more central ideas of a text and analyze their development over the course of the text, including how they interact and build on one another to provide a complex analysis; provide an objective summary of the text.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.11-12.3

Analyze a complex set of ideas or sequence of events and explain how specific individuals, ideas, or events interact and develop over the course of the text.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.11-12.7

Integrate and evaluate multiple sources of information presented in different media or formats (e.g., visually, quantitatively) as well as in words in order to address a question or solve a problem.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.11-12.4

Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.11-12.7

Conduct short as well as more sustained research projects to answer a question (including a self-generated question) or solve a problem; narrow or broaden the inquiry when appropriate; synthesize multiple sources on the subject, demonstrating understanding of the subject under investigation.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.11-12.9

Draw evidence from literary or informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.11-12.1

Initiate and participate effectively in a range of collaborative discussions (one-on-one, in groups, and teacher-led) with diverse partners on grades 11-12 topics, texts, and issues, building on others' ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.11-12.2

Integrate multiple sources of information presented in diverse formats and media (e.g., visually, quantitatively, orally) in order to make informed decisions and solve problems, evaluating the credibility and accuracy of each source and noting any discrepancies among the data.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.11-12.4

Present information, findings, and supporting evidence, conveying a clear and distinct perspective, such that listeners can follow the line of reasoning, alternative or opposing perspectives are addressed, and the organization, development, substance, and style are appropriate to purpose, audience, and a range of formal and informal tasks.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.L.11-12.1

Demonstrate command of the conventions of standard English grammar and usage when writing or speaking.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.L.11-12.4.A

Use context (e.g., the overall meaning of a sentence, paragraph, or text; a word's position or function in a sentence) as a clue to the meaning of a word or phrase.