Protesters at a Stop Asian Hate rally in Times Square.

Credit: Katie Godowski. “Stop Asian Hate Rally in Times Square.”Pexels, 16 Mar. 2022. (Free to use)

Grade: 7-10Subject:

U.S. History, Social Science

Number of Lesson Days: 3

Racial hierarchy, the white/non-white binary, and the perceived proximity to whiteness of some Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) communities have been used as a racial wedge to divide AAPIs and other communities of color. In this three-day lesson, students will consider how cross-cultural solidarity has emerged between communities in spite of this racial wedge. On Day 1, students will analyze sources to learn about historical examples of solidarity for racial justice. On Day 2, students will create a primary source mini museum to assess the impact of images and social media in building solidarity. On Day 3, students will reflect on all examples of cross-cultural solidarity studied during this unit to write a historical paper examining the role of AAPI communities in advancing racial justice.

In what ways does the Asian American and Pacific Islander community help advance racial justice?

Students will write a historical paper to examine the role Asian American and Pacific Islander communities played in advancing racial justice.

AAPIs Advancing Racial Justice Essay

Background:

Over the course of U.S. history, Asian American and Pacific Islander communities have been both discriminated against and privileged. As these communities have grown – in size and power – over time, they’ve had to choose whether they will stand in solidarity with other oppressed communities or strive to appeal to whiteness.

Essay:

While race in the United States often operates in a

hierarchy, with whiteness at the top and Blackness at the bottom, it has also operated as a white versus non-white

binary. In a racial hierarchy, some Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) communities fall closer to whiteness than other communities of color, or even other ethnic groups within the AAPI umbrella. However, when it comes to the white and non-white binary, AAPIs fall into the same category as communities of color including Latinx, Black, and Native Americans. These dynamics have allowed the AAPI community to be used as a racial wedge, dividing communities of color by privileging them over other groups – especially against the Black community. As such, communities of color are often pitted against each other instead of coalescing to fight against white supremacy. Yet, even when they are being used as a

racial wedge, AAPIs bear the impacts of

structural racism that affect, to different degrees, all non-white people in the United States.

Since the earliest AAPI communities’ existence in the United States, they have had to choose whether to align themselves with other people of color, isolate themselves, or try to appeal to white society. These choices were made out of necessity, weighing the benefits and the harms that could affect their families and wider communities. In making such choices, some AAPIs have

perpetuated anti-Black rhetoric that would allow them to distance themselves from Black communities in an effort to demonstrate and gain some

proximity to whiteness.

Yet, this choice does not protect AAPIs from structural racism in the forms of segregated schools, exclusionary immigration policies, discrimination in employment, and race-based violence. AAPIs would neither be seen nor treated as white in the United States. As such, many AAPI activists have chosen to create and accept relationships of solidarity with Black, Latinx, and Native peoples, both in the United States and beyond.

A lesser-known example of discrimination and cross-cultural solidarity is the case of Vietnamese refugee shrimpers in Galveston Bay, Texas. Some Vietnamese refugees escaping Southeast Asia after the Vietnam War settled in the Gulf Coast due to its climate and fishing and shrimping industry, both of which were familiar to many of them. However, at the time, ecological harms to the region made it harder to catch seafood, resulting in local white fishermen seeing Vietnamese fishers as unwanted competition and a threat to their livelihoods. White fishermen intimidated and harassed the Vietnamese fishers, even going as far as burning down the house of a Vietnamese family. In 1979, one of these altercations ended in the death of a white fisherman at the hands of Sau Van Nguyen (c. 1959-?) and Chihn Van Nguyen (c. 1958-?), two Vietnamese fishers. While the Nguyens were found to be acting in self-defense and were acquitted of charges, the verdict caused the

Ku Klux Klan to become involved as they sought to investigate the case for themselves.

The Klan, a white supremacist organization, was primarily known for targeting, harassing, and killing Black people. However, it has also been known to target Jewish people, immigrants, and the

LGBTQ community as an effort to maintain white power in the United States. As such, the Vietnamese refugees in Galveston Bay who were being blamed for the economic hardships of white fishers became a target of the Klan. The group openly wore their Klan robes and carried weapons as they harassed and intimidated the Vietnamese in the area. They held rallies, set fire to Vietnamese shrimp boats, burned crosses, patrolled the bay in Klan boats, and more. In other towns in the Galveston Bay, Vietnamese fishermen were similarly targeted.

The Klan held a rally in February 1981 with a thousand attendees and set fire to an

effigy of a Vietnamese boat, giving the Vietnamese ninety days to leave the Bay. Instead, the Vietnamese community and the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) sued the Klan and other individuals in the town who were behind the harassment and threats. The Vietnamese Fishermen's Association was persuaded to pursue the lawsuit when the SPLC founder Morris Dees described how Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Black community had fought for their rights in the face of Klan terrorism. This inspired the Vietnamese to fight the Klan’s harassment instead of dropping the case.

The judge in the case, Gabrielle Kirk McDonald, was a Black woman who had worked as a staff attorney with the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund. When the case was randomly assigned to her, she granted the request to

expedite it to start the hearings before the start of the shrimping season, which coincided with the Klan's ninety-day threat. Judge McDonald faced harassment and racism from Klan members, even receiving hate mail, due to her race and commitment to a fair trial. A metal detector was installed in the courthouse for the first time due to the Klan's behavior. Yet, the judge refused to step down and even worked to prevent Klan members who attended hearings from intimidating Vietnamese fishermen and SPLC lawyers in the courtroom. Judge McDonald ruled in favor of the Vietnamese Fishermen’s Association and issued an injunction against the Klan to prevent them from further harassing the fishermen, to end Klan boat patrols, and to disband the

militia that the Klan had been training. This was not only an immense victory for the Vietnamese community but also for all other groups who had been targeted by the Klan’s white supremacist violence.

Solidarity between Black and AAPI communities has not always been easy, as these two communities have been strategically pitted against each other, especially through the

Model Minority stereotype which positioned the AAPI community as high-achieving and a group to emulate. Lateefah Simon (born 1978), a Black activist in Oakland, California, said, “We don’t know each other in our communities, and we need to do a better job of humanizing each other and not pointing fingers.”

Despite barriers, solidarity between Black and AAPI communities in the fight for racial justice is notable in our history. In the 1960s, the Black Panther Party, a Black power political organization, joined forces with the Red Guard Party, a Chinese American youth organization, to push for better living conditions in San Francisco’s Chinatown. In 2014, Asians for Black Lives emerged to support Black Lives Matter (2013 to present).

In 2020, the murder of George Floyd (1973-2020), a Black man killed by a white police officer in Minneapolis, sparked a national outrage. Following his murder, there were uprisings and protests, largely led by Black Lives Matter. One of the groups who stood in solidarity with them were

K-pop fans, composed of all racial groups and nationalities but largely Asian and AAPI. BTS, one of the most popular K-pop groups, has a worldwide following and used their platform to support the cause.

After the Dallas Police Department requested people to send videos of “illegal activity from the protests” in an effort to

penalize protesters, K-pop fans flooded the app used by the police department with videos from their favorite artists, GIFs from TV shows, and more. The app system became overloaded and unusable by the police. Additionally, people began leaving one-star ratings for the app and reviews with anti-police and pro-Black Lives Matter messages.

In another instance, K-pop fans used their social media reach to take over and drown out the “whitelivesmatter” hashtag on Twitter (now known as X). Thousands of K-pop fans tweeted using their hashtag to post anti-racist videos and messages, as well as memes, GIFs, and videos from their favorite artists, to effectively bury white supremacist posts.

In both examples, K-pop fans used their knowledge of social media

algorithms to quickly mobilize the massive fandoms of various Korean pop groups to support the Black community’s demands for racial justice. These acts of solidarity fall into the larger context of AAPIs across the United States supporting the demands of the Black Lives Matter movement, just as communities of color have supported rallies and marches demanding an end to anti-Asian violence.

With the outbreak of the COVID-19 in late 2019, there was racist

rhetoric (i.e., referring to COVID as “Kung Flu” or the “China Virus”) blaming Asians and Asian Americans for the pandemic. This led to escalating anti-Asian hate against AAPIs, especially the elder community. This hate manifested as attacks, verbal assaults, spitting, etc. The Stop Asian Hate campaign (2021 to present) emerged as a slogan and name for a series of demonstrations, protests, rallies, and more. In 2021, a gunman killed eight people at spas in Atlanta, Georgia - six of the victims were Asian American women. In response to the Atlanta spa shooting, people across the country took up “Stop Asian Hate” slogans, hosting vigils, marches, and more in honor of the victims. Additionally, volunteers from all racial groups stepped up to safely escort AAPI elders, provide neighborhood patrols, and more. In New York City, Black filmmaker and activist Coffey dedicated his monthly "Running to Protest" event to addressing the surge in anti-Asian violence and building Black and Asian solidarity. Coffey founded Running to Protest in 2020 after the murder of George Floyd and organized monthly runs to raise awareness of different causes and issues. The March 2021 run was attended by over 1,000 people who championed safety for Asian communities alongside slogans of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Despite these moments of solidarity and struggling together, the use of AAPIs as a racial wedge will continue to be an issue so long as AAPIs adopt anti-Blackness and allow themselves to be used to denigrate other communities of color. This anti-Blackness is often rooted in a lack of understanding of the racial dynamics and history of the United States, especially as it pertains to the historic and continual discrimination against and disenfranchisement of Black people. Additionally, some AAPIs may be more motivated to gain social and economic mobility in the United States than to challenge issues that they don’t believe affect them. However, in order to achieve a more equitable and just future, building solidarity with other communities is key. It is necessary to recognize, acknowledge, and repair the rifts between communities, and among other communities of color, that are caused by white supremacy and continue to build relationships of

transformational solidarity.

Bibiliography:

- Algorithm: method of sorting posts in a users’ feed based on relevancy instead of published time

- Binary: having only two options or parts

- Effigy: an image or representation especially of a person

- Expedite: to speed up or execute promptly

- Hierarchy: system of ranking

- K-pop: Korean pop music and culture

- Ku Klux Klan: an American white supremist group known for targeting violence against people of color

- LGBTQ: lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning (one's sexual or gender identity)

- Militia: a military force of civilians

- Model Minority stereotype: inaccurate depiction of AAPIs as a “model” while diminishing other groups

- Penalize: to inflict a penalty on

- Perpetuated: cause to continue or last indefinitely

- Proximity: closeness

- Racial Wedge: the process of splitting up communities of color or pitting them against each other

- Rhetoric: language designed to persuade

- Structural Racism: forms of racism that are pervasively and deeply embedded in systems, laws, written or unwritten policies

- Transformational Solidarity: when oppressed communities forgo something that would benefit them because it comes at the expense of other oppressed communities

- What is a racial hierarchy? How does this affect Asian American and Pacific Islander communities?

- What does it mean to be a racial wedge? How does this affect AAPI communities?

- Why and how would Asian American and Pacific Islander communities perpetuate anti-Blackness?

- What happened to the Vietnamese refugee shrimpers in Galveston Bay, Texas? How was this an example of cross-cultural solidarity?

- What serves as a barrier between Black and AAPI solidarity?

- What are examples of Black and AAPI solidarity?

- How did K-pop fans support Black Lives Matter?

- Why did the Stop Asian Hate campaign form? How did communities of color support Stop Asian Hate?

- Why might some Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders succumb to anti-Blackness? What needs to change?

Activity 1: Introduction to the Lesson

- Tell students that since the COVID-19 pandemic broke out in the U.S. in 2020, there has been a huge increase in hate crimes and hate incidents against the Asian American and Pacific Islander community.

- Show the video entitled, “#StopAsianHate Together”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Ps1D-hESes&t=3s

- NOTE TO TEACHER: If needed, give students a content warning about the video, as it mentions acts of hate and violence against Asian American and Pacific Islander communities.

- Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- What is the message of this video?

- Was the presentation effective in conveying the message?

- What was the point of sharing the examples of hate crimes against the Asian American and Pacific Islander communities over the course of U.S. history?

- What does the quote mean: “Solidarity is the answer to silence”? (Clip 2:28)

A Vietnamese Fisherman's Family in Seadrift, Texas, 1978.

Activity 2: AAPIs Advancing Racial Justice

- Distribute the text entitled, “AAPIs Advancing Racial Justice.”

- Have students read the text and direct them to annotate by doing the following:

- Underline key words

- Circle confusing words and concepts

- Write questions and summaries in the margins

|

Strategy: Annotating

Annotating is a strategy for careful or close reading. Students are required to actively transact with the text. Annotating allows students to easily reference texts for future writing tasks as they can use their notes versus having to re-read texts.

For more on annotating, see:

|

- NOTE TO TEACHER: If time is limited, have students complete the reading for homework the night before.

- Facilitate a discussion by asking the Discussion Questions.

- NOTE TO TEACHER: The text mentions the Model Minority stereotype which is the notion that Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders are “smart” and “hardworking.” They have achieved success through hard work and determination and thus suitable models for other minorities to emulate. This idea serves as a racial wedge as it pits Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders against other communities of color, especially against the Black community. By even referring to one group as a “model” diminishes other groups. If students need more support in understanding the Model Minority stereotype, consider teaching this lesson (or relevant parts of the lessons) from The Asian American Education Project: “Model Minority Myth”: https://asianamericanedu.org/3.1-Model-Minority-Myth-lesson-plan.html

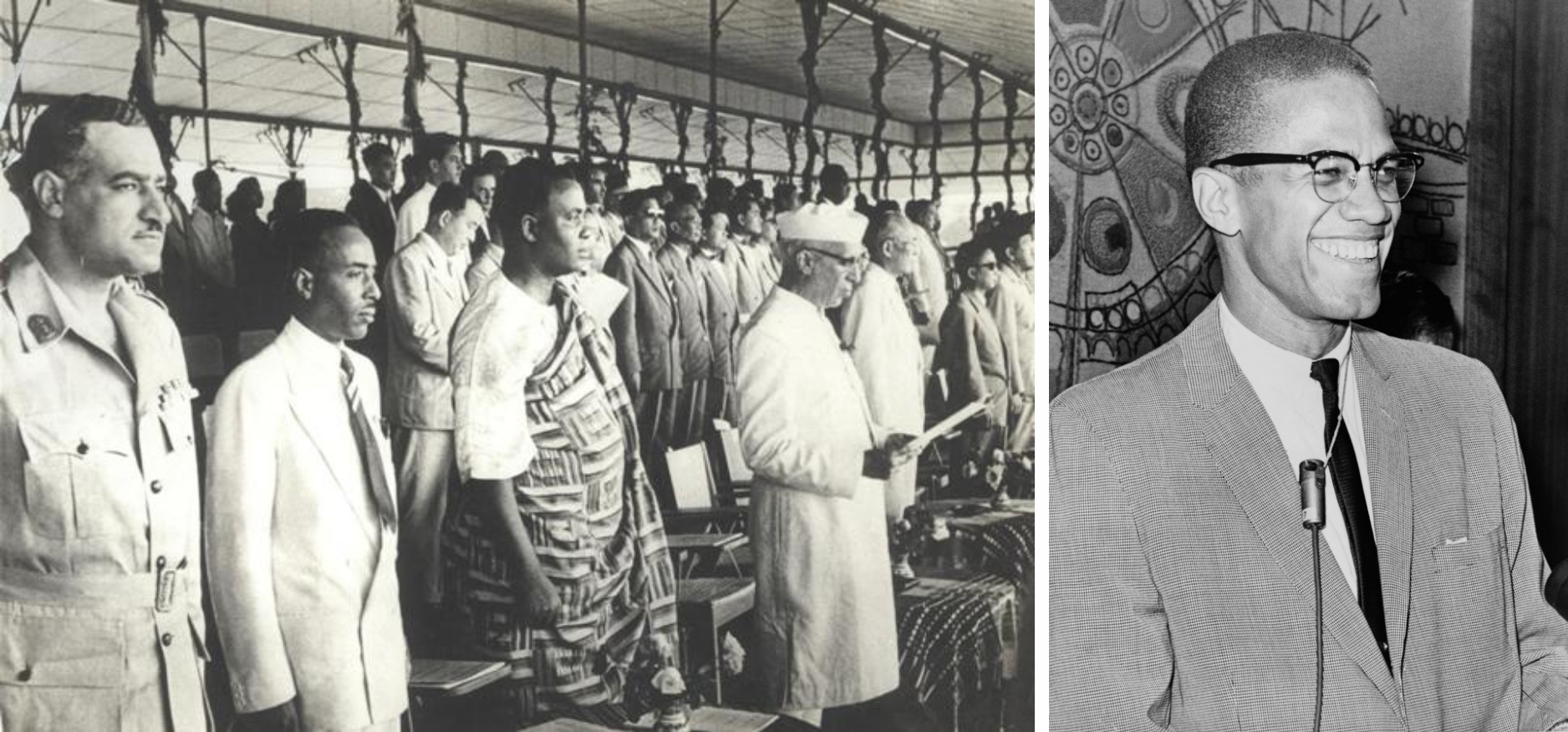

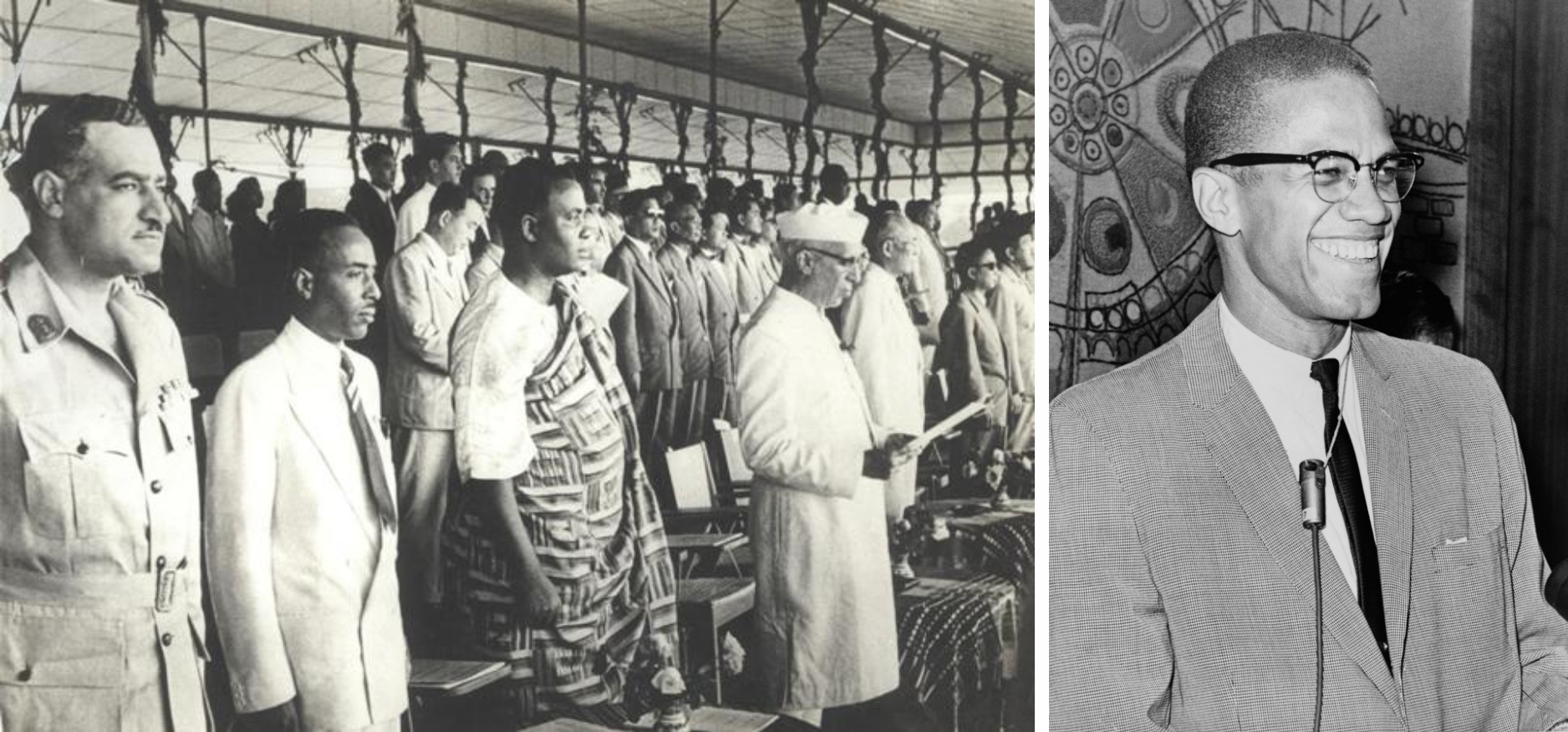

Left - Participants of the Afro-Asian Conference (Bandung Conference) in Bandung, Indonesia, April 1955.

Credit: Unknown Author (Public Domain). “Asian–African Conference at Bandung April 1955.” via Wikimedia Commons.

Right - Photo of Malcolm X.

Credit: Library of Congress. “Malcolm X NYWTS 2a.” via

Wikimedia Commons, 12 March 1964. No copyright restriction known.

Activity 3: Analyzing Sources on the Bandung Conference

- NOTE TO TEACHER: If time is limited, skip this activity and go straight to Activity 4.

- Distribute the texts and worksheet entitled, “Bandung Conference and Malcolm X.”

- Tell students that they will be reading a primary source (firsthand account) and a tertiary source (text that summarizes primary and secondary sources).

- Tell students to read the texts and direct them to complete the worksheet:

- Record observations in the left column.

- Record questions in the right column.

- Annotate as you read by highlighting or underlining important ideas and circling confusing vocabulary and concepts.

- Write a summary in your own words.

|

Strategy: Analyzing Sources

(Observe, Reflect, Question Strategy)

Primary and secondary sources can be complex texts. But, they are necessary for historical thinking. Both sources complement each other in order to help learners build convincing arguments. Teachers can help students by providing prompting questions as they read.

For more on analyzing sources, see:

|

Activity 4: Share What You’ve Learned

- Have students share the following with a partner:

- Share three things you have learned from this lesson so far.

- Share two questions you have about the content.

- Share one thing you would like to challenge or one thing that resonated with you personally.

|

Strategy: 3-2-1

A 3-2-1 strategy is a protocol for student response. It provides teachers with a check for understanding. As a prompt, it helps students structure their responses to a text, film/video, or lesson by asking them to describe three takeaways, two questions, and one thing they enjoyed. The content can be adapted as needed.

For more on analyzing sources, see:

|

- NOTE TO TEACHER: If students need more background about Asian American and Pacific Islander activism and solidarity, consider teaching the following lessons:

- “Asian Americans as Activists and Accomplices”: https://asianamericanedu.org/activists-activism-accomplices.html

- “Powerful Individuals, Powerful Movement”: https://asianamericanedu.org/movements-against-injustice.html

- “Building Community Consciousness and Coalitions”: https://asianamericanedu.org/building-community-consciousness-and-coalitions.html

Activity 1: The Role of Social Media in Fighting for Racial Justice

- Ask students to review the use of social media mentioned in the text entitled, “AAPIs Advancing Racial Justice” by asking:

- How did K-pop fans use their social media?

- In what ways can social media be a tool for solidarity work?

- Why is social media an effective tool for solidarity?

- How can you use your social media to support others?

A multiracial coalition of people with signs that read “Stop Asian Hate” and “Love Over Hate.”

Credit: “03.20.21_Solidarity Against Hate Crimes (151)” by Paul Becker,

CC BY 2.0 DEED via flickr, 21 March 2021.

Activity 2: Primary Source Mini-Museum

- Tell students that social media and images have been powerful tools, especially within the past four years, with the heightened presence of the Black Lives Matter and Stop Asian Hate movements.

- Distribute the worksheet entitled, “Primary Source Mini-Museum.”

- Direct students to find an image or a social media post related to cross-cultural solidarity evident in the Black Lives Matter and Stop Asian Hate movements since 2020.

- Have students complete the worksheet. Direct them to answer the following questions on a separate sheet of paper:

- What is it? (photograph, artwork, or social media post)

- Who created the source?

- Who or what is the source about?

- What perspective is shown in this source?

- What is the purpose or function of this source?

- When was this source created?

- Who is the intended audience of this source?

- Have students complete the bottom half of the worksheet by creating a museum-style label:

- Write a caption: In a sentence or less, write an explanation or title for the primary source.

- Description: Write three to four sentences explaining the primary source’s significance.

|

Strategy: Primary Source Mini-Museum

This strategy is a creative way for students to closely examine a primary source and to summarize content. Summarizing is an important skill because students need to understand and learn important content by reducing information to its key ideas.

For more on the Primary Source Mini-Museum, see:

|

- NOTE TO TEACHER: If needed, model how to complete this activity by referring to the worksheet entitled, “Example: Primary Source Mini-Museum.”

Activity 3: Gallery Walk

- Have students finalize their caption and description.

- Have students create a flyer that includes their image or social media post and the finalized version of their caption and description.

- Facilitate a Gallery Walk by hanging their flyers around the room.

- Have students walk around the room and view the flyers.

- Have students place post-it notes to add comments and questions on each visual.

|

Strategy: Gallery Walk

Gallery Walks are an active learning strategy. During a gallery walk, students explore multiple texts or images that are placed around the room. Students are able to share their work with peers, examine multiple content, and/or respond to multiple content. Because this strategy requires students to physically move around the room, it can be especially engaging to kinesthetic learners.

|

- Have students find a partner and share at least three new things they learned from the Gallery Walk.

- Allow students time to find and read sources and to complete the worksheet.

- Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- How are images a powerful tool for change? What do they reveal about cross-cultural solidarity?

- How are social media postings a powerful tool for change? What do they reveal about cross-cultural solidarity?

- What do images and social media postings reveal about the Black Lives Matter movement? What do they reveal about the Stop Asian Hate movement?

- Which do you think is a more effective tool: images or social media posts? How so?

Activity 4: Quickwrite

- Have students complete a Quickwrite given these prompts: Why did you select the image or social media posting that you did?

|

Strategy: Quickwrite

A Quickwrite is an instructional practice that allows students an opportunity to quickly respond to a question or prompt. It is often timed for 3-10 minutes. It provides teachers an assessment of what students know or think at that moment in time. It provides students an opportunity to freely write down their first thoughts. It can be used at any time in a lesson.

|

- Allow students an opportunity to share what they wrote in their Quickwrites.

- Tell students that there are different ways to support a cause and encourage them to use the tools and resources available to them.

Fans of the K-pop band BTS have used online platforms to show solidarity with Black Lives Matter.

Credit: “BTS at the White House on May 31, 2022.” The White House (Public Domain).Wikimedia Commons, 31 May 2022.

Activity 1: Cross-Cultural Solidarity Examples

- Have students collect all their notes, worksheets, readings, etc. from the entire unit. Tell them to make a list or take note of all the examples of cross-cultural solidarity that they have learned about throughout the unit.

- Create and display the following chart for all to see:

|

Examples of AAPIs standing in solidarity to support causes of other communities of color:

|

Examples of AAPI and communities of color standing in solidarity to support a common cause:

|

Examples of other communities of color supporting AAPI causes:

|

Examples of AAPI communities being inspired by the actions of other communities of color:

|

Examples of other communities of color being inspired by the actions of AAPI communities:

|

|

|

|

|

|

- Direct students to complete the chart by sorting all the examples of cross-cultural solidarity into the following categories:

- Examples of AAPIs standing in solidarity to support the causes of other communities of color

- Examples of AAPI and communities of color standing in solidarity to support a common cause

- Examples of other communities of color supporting AAPI causes:

- Examples of AAPI communities being inspired by the actions of other communities of color

- Examples of other communities of color being inspired by the actions of AAPI communities

- NOTE TO TEACHER: Here is an answer key for the chart:

|

Examples of AAPIs standing in solidarity to support causes of other communities of color:

|

Examples of AAPI and communities of color standing in solidarity to support a common cause:

|

Examples of other communities of color supporting AAPI causes:

|

Examples of AAPI communities being inspired by the actions of other communities of color:

|

Examples of other communities of color being inspired by the actions of AAPI communities:

|

|

#NODAPLprotests

Japanese Americans against Islamophobia + racial profiling

|

Filipino & Mexican farmworkers

NYC Taxi Driver Strike

Third World Liberation Front

Present-day immigration reform/rights for undocumented immigrants

Bandung Conference |

I-Hotel Protests

Buffalo Soldiers in the Philippines

Mauna Kea protests

Vietnamese shrimpers

Douglass & the Chinese Exclusion Act

Mexican-Punjabi intermarriage

Black and Jewish Americans against Japanese American incarceration |

Yellow Power movement inspired by Black Power movement |

I-Hotel Protests

K-pop fans’ Twitter storms/ video flooding |

Activity 2: Historical Significance Tool

- Share the following statement: “Everything that has ever happened is history. There is too much history to remember. As such, historians focus on significant events. Significant events are those that have resulted in great change over long periods of time for large numbers of people. Significance depends on one’s perspective and purpose. Significance can also be debated.”

- NOTE TO TEACHER: If students need help understanding this concept of significance, have them recall a significant event in their own lives and question them on why these events were significant and how they determined their significance.

- Tell students they will be writing an essay or paragraph given the following prompt: Which example of cross-cultural solidarity most significantly demonstrates the role Asian American and Pacific Islander communities played in advancing racial justice?

- Distribute the worksheet entitled, “Historical Significance Tool.”

- Explain the criteria for determining significance (left column) - tell students that these criteria are not definitions but guidelines for thinking historically:

- Importance - This measures the impact on the lives of those living at the time. Encourage students to empathize with the people in the past to more clearly assess their perspective and context.

- Profundity - This measures how deeply people were impacted. It doesn’t matter if the event was negative or positive.

- Quantity - This measures the number of people affected. Make sure students understand that quantity does not mean quality.

- Durability - This measures the impact of past events on subsequent events and the present. Make sure students understand that short-lived events can have great long-lasting effects.

- Relevance - This measures the significance of an event to the present.

- Tell students to refer to the texts read in this lesson as evidence of their thinking.

- Tell students to evaluate the criterion in the right column with a “yes” or “no.”

- Tell students to answer the question in Part 2: Was this event or case historically significant?

|

Strategy: Historical Significance Tool

Significant events are those that have resulted in great change over long periods of time for large numbers of people. Significance depends on one’s perspective and purpose. The Historical Significance Tool helps students make an argument for whether a particular event is considered significant.

For more on the Historical Significance Strategy, see:

|

- Tell students that if their chosen event turns out not to be as significant as they would like, they should repeat the worksheet with another event.

Activity 3: Structured Historical Paragraph Tool

- Distribute the worksheet entitled, “Structured Historical Paragraph Tool.”

- Tell students they will be writing an essay or paragraph given the following prompt: Which example of cross-cultural solidarity most significantly demonstrates the role Asian American and Pacific Islander communities played in advancing racial justice?

- Have students refer to their notes from the “Historical Significance Tool.”

- Have students select the topic that they think is the most significant contribution.

- Have students use their notes to provide evidence for their thinking and to explain the economic, social, political, and cultural forces at play.

- Give students time to complete each section of the worksheet:

- Topic Sentence: Introduce the topic/main idea that you will explain in the paragraph.

- Historical Context: Provide background information to help the reader better understand the historical forces.

- Introduce the Evidence: Provide background about the evidence that will help your audience to better understand it.

- Evidence: Provide the fact(s) that support the topic sentence. Citations should be provided.

- Discussion: Discuss/Analyze the ideas presented in the evidence.

- Have students turn the notes they wrote on the worksheet entitled, “Structured Historical Paragraph Tool” into a final product.

- NOTE TO TEACHER: If needed, provide feedback on the worksheet before having students finalize their writing. Another option is to allow students to peer review each other’s work.

|

Strategy: Structured Historical Paragraph Tool

The Structured Historical Paragraph Tool supports students as they engage in historical writing. The tool guides students in thinking about the required essential elements of a historical paragraph. It helps students organize their thoughts into a cohesive structure.

|

Activity 4: Summary of Lesson

- Allow students an opportunity to summarize what they think is the most significant example of cross-cultural solidarity and why.

- Ask students: Was it challenging to pick just one event or action? Why or why not? Why would it be valuable to think about significance?

- Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- What was the most significant thing you learned over the course of the unit?

- What idea challenged you the most?

- What idea confused you the most?

- What would you like to learn more about?

- Summarize the Cross-Cultural Solidarity unit by sharing this statement: “Over the course of this unit, we have learned about how and why communities of color have coalesced to improve their conditions and to combat hate and discrimination. We have discussed ways different communities challenged exclusion, unfair labor practices, imperialism, war and violence, educational inequities, and racial injustice. We have learned that there are different tactics and ways that people can show up for each other and that solidarity is hindered by barriers and potential risks. There are many more issues that can be learned. Hopefully, one of the main things that you have learned from this unit is that Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders are a significant part of the American narrative and their histories and narratives deserve to be told and taught.”