Users agree to attribute work to AAEdu and National Archives.

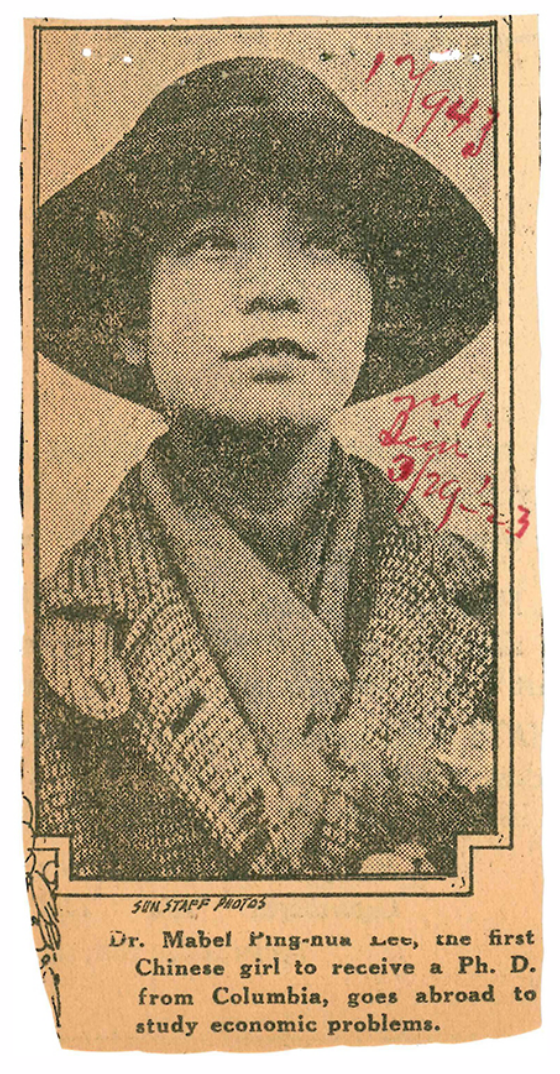

This newspaper clipping shows Dr. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee, a Chinese American feminist and activist in the women’s suffrage movement.

Image Credit: DocsTeach, National Archives (Public Domain)

Grade: 8-12Subject:

U.S. History, Social Studies, English Language Arts

Number of Activities: 5

Born in Guangzhou, China, Dr. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee (1896-1966) was a Chinese American suffragist. She advocated and organized for women’s right to vote in the United States. A pioneer in the women’s suffrage movement, her contributions are often overlooked. In this lesson, students will learn about the history and contributions of Lee. Students will examine how anti-Chinese legislation like the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 impacted Chinese immigrants like Lee. Students will read two pieces of Lee’s writing and analyze her contributions to the women’s suffrage movement.

Students will:

- Describe the accomplishments and contributions of Mabel Ping-Hua Lee.

- Explain how the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 impacted Mabel Ping-Hua Lee.

- Analyze Mabel Ping-Hua Lee’s writing and her role in the women’s suffrage movement.

Dr. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee Essay:

Dr. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee (1896-1966) was a Chinese American

suffragist. She advocated and organized for women’s right to vote in the United States. She was a pioneer in the women’s suffrage movement. Yet, not many people know who she is.

Lee was born in Guangzhou, China (previously known as Canton, China). Her father was a

minister and a

missionary. He moved to the United States when Lee was four years old. Lee stayed in China with her mother and grandmother. When she was nine years old, Lee won a

scholarship to go school in the United States. In 1905, her family moved to Chinatown in New York City. Lee attended Erasmus Hall Academy in Brooklyn, New York. Her father continued his ministry work in New York, and became a community leader in Chinatown.

During this period the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was in effect. This law banned Chinese from entering the United States with a few exceptions. Lee’s parents were able to immigrate because they were teachers working for the Baptist Church. The Chinese Exclusion Act also prevented Chinese immigrants already in the United States from becoming

citizens. The Chinese Exclusion Act reflected the anti-Chinese sentiment of the time. Many White laborers saw the Chinese as an economic threat and as foreigners.

Because of the Chinese Exclusion Act, Lee and her family were one of few Chinese families in New York at the time. They could not become citizens and could not vote.

While in school, Lee learned about activism and women’s rights. Her family also stayed informed about current events and issues in China, and so Lee became knowledgeable about women’s rights in both countries. In 1912, when she was sixteen years old, she helped lead a suffrage parade on horseback in New York City. Lee organized a

delegation of Chinese American women to participate in the march. Almost 10,000 people attended the parade. The

New York Tribune and

The New York Times published articles about her activism and leadership in 1912.

Soon after, Lee attended Barnard College in New York City where she studied history and philosophy. She became active in the Chinese Students’ Association and wrote essays for The Chinese Students’ Monthly, the first magazine published by Chinese students in the United States. In one of her essays, “The Meaning of Woman Suffrage,” Lee laid out her arguments for women’s equality and why women’s suffrage was important for democracy. In 1915, Lee gave a speech called, “The Submerged Half” (or “China’s Submerged Half”) at the Women Political Union’s Suffrage Shop. In her speech, she urged the Chinese community to support girls’ and women’s education as well as civic engagement.

Lee went on to earn a master’s degree from Teachers College at Columbia University, and later a Ph.D. in economics from Columbia. She is the first Chinese American woman to earn a Ph.D. in economics. In 1921, Lee published her research in a book called The Economic History of China.

In 1917, New York State granted women the right to vote. In 1920, the U.S. Congress

ratified the 19th Amendment, granting women across the country the right to vote. However, that right did not extend to Chinese women and some other women of color and immigrant communities. This is because voting required U.S. citizenship. Because the Chinese Exclusion Act prevented Chinese immigrants from becoming citizens, Chinese women could not vote. Chinese women did not have the right to vote until the Chinese Exclusion Act was

repealed in 1943. Nonetheless, Lee continued to push for women’s rights.

Lee had hoped to return to China and advocate for Chinese women there. However, her father died in 1924, and she took over his role as director of the First Chinese Baptist Church of New York City. She later founded the Chinese Christian Center, a community center that offered a health clinic, kindergarten, job training, and English classes for the Chinese American community in New York City.

Lee died in 1966 when she was 70 years old. It is unknown if she ever became a citizen or voted in the United States. While she may not have ever voted herself, Lee leaves behind a legacy of championing women’s rights and fighting for equality.

Bibliography:

- Citizen: a native or naturalized person who owes allegiance to a government and is entitled to protection from it

- Delegation: a group of persons chosen to represent others

- Democracy: a form of government in which the people elect representatives to make decisions, policies, laws, etc., according to the law

- Minister: a person officiating in church worship

- Missionary: a person commissioned by a religious organization to spread its faith or carry on humanitarian work

- Ratify: to approve and sanction formally

- Repeal: to rescind or annul by authoritative act

- Scholarship: a grant-in-aid to a student

- Suffragist: one who advocates extension of the right to vote, especially to women

- What was Lee’s early life like?

- What was the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882?

- How did the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 impact Lee’s family?

- How did Lee contribute to the women’s suffrage movement as a young person?

- What were Lee’s academic accomplishments?

- What is the 19th Amendment?

- Why did the 19th Amendment not extend voting rights to Chinese women?

- How did Lee support her community in Chinatown?

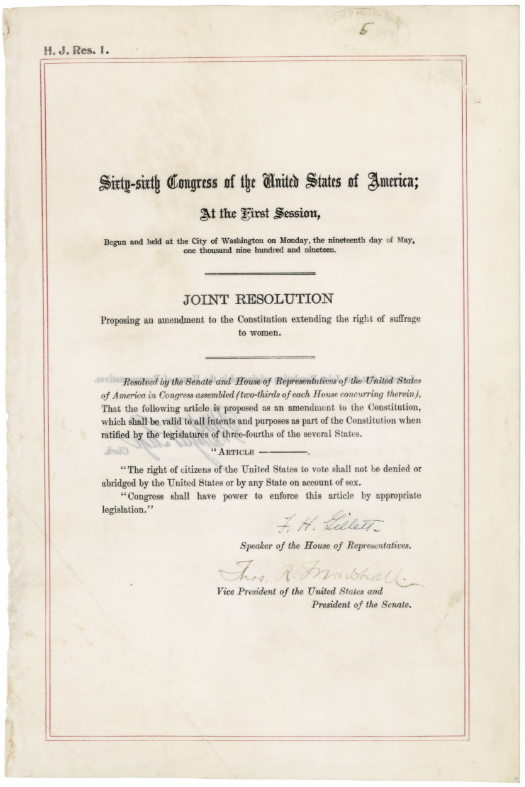

The 19th Amendment, ratified in 1920, legally guarantees American women the right to vote. However, other legislation at the time prevented this right from extending to all women.

Image Credit: DocsTeach, National Archives (Public Domain)

Activity 1: Examining the Right to Vote

- Have students write a Quickwrite in response to the following prompt: “Why is voting important? Why is the right to vote important?”

- Show the video entitled, “19th Amendment: 'A Start, Not A Finish' For Suffrage” by NPR.

- Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- Why is voting an integral part of democracy?

- How would you describe the path to voting rights in U.S. history?

- Why have people fought so hard for the right to vote in the United States?

- How have race and sex intersected or been in conflict in the fight for voting rights?

- Distribute the worksheet entitled, “Voting Amendments.”

- Assign students to work in small groups. Have each group use information from the video and additional internet research to complete the worksheet.

- Have students describe the gist of the Amendment in the “What is it?” column.

- Have students list groups the Amendment extended voting rights to in the “Who did it include or benefit?” column.

- Have students list groups the Amendment did not extend voting rights to in the “Who did it exclude?” column.

- Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- What patterns do you notice in the Amendments?

- Who benefits and who doesn’t? Why is this so? What are the reasons for the disparities?

- Why would a government want to prevent people from voting?

- How is voting a source of power in a democracy?

Women’s suffrage parade in New York City in 1912. When Lee was sixteen years old, she helped lead a suffrage parade on horseback.

Image Credit: DocsTeach, National Archives (Public Domain)

Activity 2: Examining Photographs of Women’s Suffrage

- Display the following images of women’s suffrage marches:

- New York City, 1912: Suffrage Parade in New York City

- Washington, DC, 1913: Women Marching in Suffrage Parade in Washington, DC

- New York City, 1913: Suffrage Parade

- Harrisburg, PA, 1919: Central Pennsylvania Women's Suffrage Association Joins the Red Cross Parade

- Have students closely examine each photograph and read the text below each photograph. Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- What do you see in the photo?

- What inferences can you make from the photo?

- How does the historical context help you make sense of the photo?

- Who is represented in these photos? Who is missing?

- Have students write a Quickwrite in response to the following prompt: “How can a women’s movement be inclusive? How can a women’s movement be exclusive?” Have students share their responses.

- Tell students the following: “Throughout U.S. history, many people have fought for voting rights. In particular, many advocated for women’s suffrage. However, the women’s suffrage movement has often focused on White women and prioritized winning women’s right to vote even when it excluded many women of color. Women of color have also fought for women’s suffrage even when they themselves didn’t benefit. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee was one of these women. She was a trailblazer in the women’s suffrage movement.”

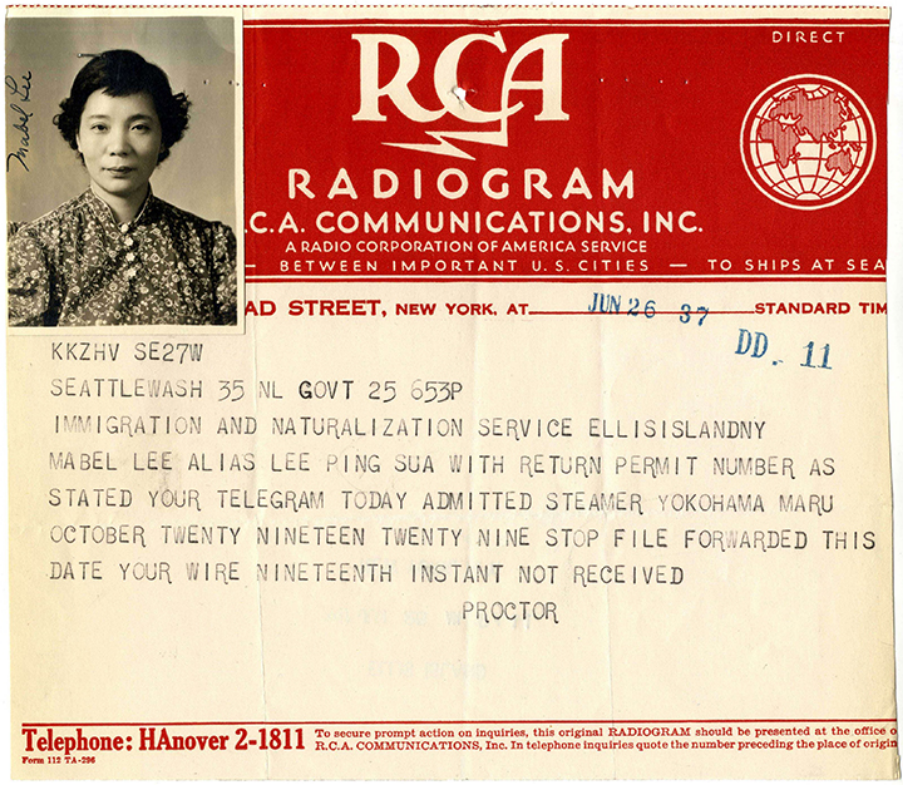

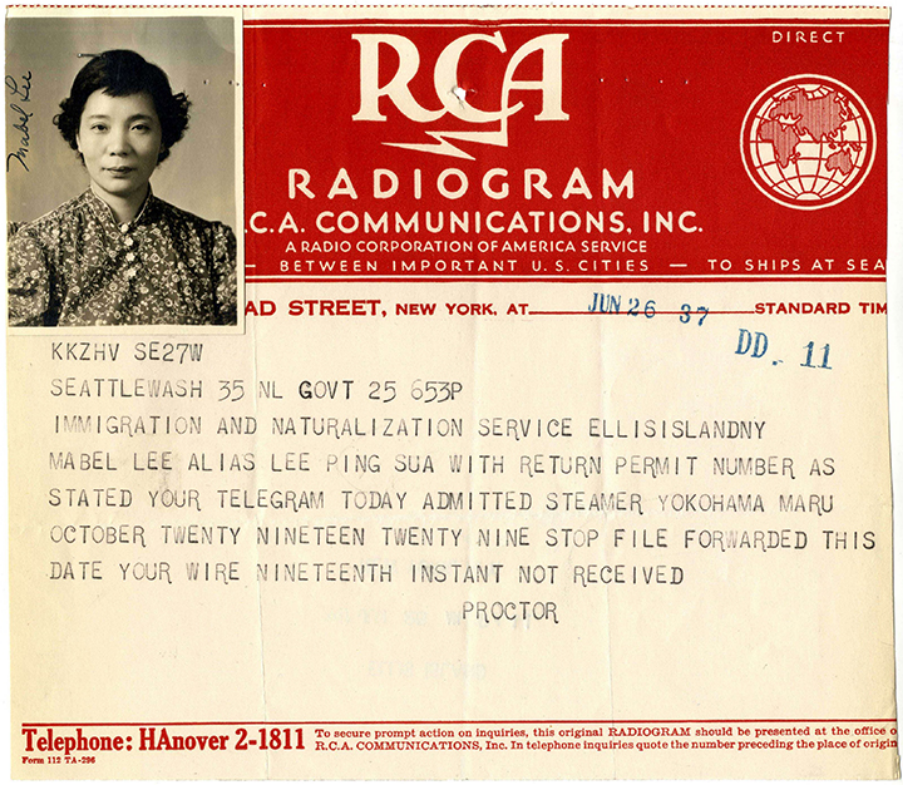

This radio telegram confirmed for the Immigration and Naturalization (INS) Service that Mabel Lee had boarded the steamer Yokohama Maru on October 20, 1929. Due to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, Chinese immigrants were required to apply for certifications for reentry and complete an interview in order to leave and return to the United States.

Image Credit: DocsTeach, National Archives (Public Domain)

Activity 3: Learning about Dr. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee

- Have students read the essay. Consider the following options:

- OPTION 1: Have students read the essay independently either for homework or during class time.

- OPTION 2: Read aloud the essay and model annotating.

- OPTION 3: Have students read aloud in pairs or small groups.

- Facilitate a class discussion by asking students the Questions.

- Divide students into three groups and assign each group one of the following documents:

- Group 1: Application for Reentry Permit for Mabel Ping-Hua Lee

- Group 2: Interview of Mabel Ping-Hua Lee

- Group 3: Radiogram about Mabel Ping-Hua Lee

- Distribute the worksheet entitled, “Document Analysis.” Have students examine their assigned document and read the explanatory text below the document. Have students complete the worksheet:

- Have students write the title and date of the document in the top row.

- Have students write the type of document in the second row.

- Have students write a summary and purpose of the document in the third row.

- Have students respond to the following question in the last row: “How did the Chinese Exclusion Act impact Lee?”

- Reconvene after as a whole group and have each group share a summary of their document, making note of the different responses.

- Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- What do these documents reveal about how the Chinese Exclusion Act impacted Chinese immigrants in the United States?

- What do these documents reveal about anti-Chinese and anti-immigrant sentiment at the time?

- What do these documents reveal about Lee’s struggles and triumphs?

- Why is Lee’s story overlooked?

Activity 4: Analyzing Lee’s Writing

- Distribute the worksheet entitled, “Primary Source Analysis.”

- Divide students into two groups and assign each group one of the following writings by Lee. Have students read their assigned text.

- Group 1: “The Meaning of Woman Suffrage” (1914)

- Group 2: “China’s Submerged Half” (1915)

- Have students work in small groups to complete the Primary Source Analysis.

- Have students write information related to sourcing in the “Sourcing” section to include:

- Type of document

- Title of document

- Author

- Date

- Intended audience

- Have students respond to the following questions in the “Contextualizing” section:

- What was happening at the time this was written? Explain the historical context.

- How does this document fit into and explain that historical context?

- Have students respond to the following questions in the “Analyzing” section:

- What claims does the author make?

- What evidence does the author make to support their claims?

- What language (word choice, phrases, etc.) does the author use to support their claims?

Assign students to work in pairs with one person representing each of the two texts. Have partners share their Primary Source Analysis of their assigned text.

Reconvene as a whole class. Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- Why does Lee believe women’s rights are important to democracy? How does she make her case?

- How did Lee use her platform to speak out?

- In what ways was Lee effective in communicating her message?

- What role did Lee play in upholding democratic ideals?

- How did Lee’s personal experience and/or culture impact her political agenda?

Dr. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee, ca. 1920-1925.

Image Credit: Library of Congress (No known restrictions on publication)

Activity 5: Interpreting Significant Quotes from Lee

- Have students select one quote from one of Lee’s writings that stands out to them. Have them complete the worksheet entitled, “Significant Quote.”

- Have students copy the quote in large text in the top row and cite the source of the quote.

- Have students respond to the following questions on the second row:

- What does it mean? (What are the figurative, connotative, and technical meanings of the words in this quote?)

- What is her point of view, purpose, or argument in this quote?

- What is her evidence?

- Have students write a news article explaining Lee’s life and legacy. Have students include their selected quote in the article.

- Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- What is Lee’s legacy?

- How was Lee a trailblazer in the women’s suffrage movement?

- Why is it important to learn Lee’s story?

- Have students learn about the renaming of the Manhattan Chinatown Post Office in 2018 to “The Mabel Lee Memorial Post Office.” Have students read the article entitled, “Post Office Named for Chinese American Leader in Suffrage Movement” and view images from the dedication ceremony in the article entitled, “Dedication of Mabel Lee Post Office in Pictures.” Have students analyze the significance of the dedication and renaming.

- Show the video entitled, “Voting is Your Privilege: Unsung Heroes” by 1990 Institute. Ask students, “What is the connection between Mabel Ping-Hua Lee and Tye Leung Schulze?” Have students compare and contrast the stories and activism of Lee and Schulze. Have students identify other unsung heroes in the women’s suffrage movement.

- Show the video entitled, “When voting rights didn't protect all women” by Vox. Have students create a timeline of when various groups of women gained the right to vote. Have students research groups who do not have the right to vote currently (ie. non-citizens, people under age 18, people incarcerated in federal or state facilities), and/or voter restriction laws. Have students write an Op-Ed about the current state of voting rights and how voting rights should or should not be expanded.

- Have students research the history of women’s suffrage in China during Lee’s lifetime. Have students compare and contrast the experience of women in China versus the United States. Ask students, “What could Lee have done for the suffrage of Chinese women? What were her limitations?”

D2.Civ.2.9-12.

Analyze the role of citizens in the U.S. political system, with

attention to various theories of democracy, changes in Americans’ participation

over time, and alternative models from other countries, past and present.

D2.Civ.10.9-12.

Analyze the impact and the appropriate roles of personal

interests and perspectives on the application of civic virtues, democratic

principles, constitutional rights, and human rights.

D2.Civ.14.9-12.

Analyze historical, contemporary, and emerging means of

changing societies, promoting the common good, and protecting rights.

D2.His.1.9-12.

Evaluate how historical events and developments were shaped by

unique circumstances of time and place as well as broader historical contexts.

D2.His.12.9-12.

Use questions generated about multiple historical sources to

pursue further inquiry and investigate additional sources.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.9-10.2

Determine the central ideas or information of a

primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of how key events or

ideas develop over the course of the text

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.9-10.4

Determine the meaning of words and phrases as

they are used in a text, including vocabulary describing political, social, or

economic aspects of history/social science.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.9-10.8

Assess the extent to which the reasoning and

evidence in a text support the author's claims.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.9-10.4

Determine the meaning of words and phrases as

they are used in a text, including figurative, connotative, and technical meanings; analyze the cumulative impact of specific word choices on meaning and tone (e.g., how the language of a court opinion differs from that of a newspaper).

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.11-12.2

Determine the central ideas or information of a

primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary that makes clear the

relationships among the key details and ideas.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.11-12.4

Determine the meaning of words and phrases as

they are used in a text, including analyzing how an author uses and refines the

meaning of a key term over the course of a text

8.2e

Progressive reformers sought to address political and social issues at the

local, state, and federal levels of government between 1890 and 1920. These

efforts brought renewed attention to women’s rights and the suffrage movement

and spurred the creation of government reform policies.

- Students will explore leaders and activities of the temperance and

woman’s suffrage movements.

10.3 d

Social and political reform, as well as new ideologies, developed in

response to industrial growth.

- Students will investigate suffrage, education, and labor reforms, as well

as ideologies such as Marxism, that were intended to transform society.

11.5 b

Rapid industrialization and urbanization created significant challenges and

societal problems that were addressed by a variety of reform efforts.

- Students will examine the efforts of the woman’s suffrage movement

after 1900, leading to ratification of the 19th amendment (1920).