2.6.2 - Pretext for the Incarceration of Japanese Americans

SPEAKING OUT - A panel of representatives of the National Coalition for Redress / Reparations San Diego chapter speak at the Commission on the Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians hearings in August 1981 at the State Building in Los Angeles. Photo by Roy Nakano

Source

Grade: 11Subject:

U.S. History

Number of Lessons: 4

This unit will expose students to the life of Fred Korematsu and have them determine whether the treatment of Japanese Americans, majority of whom were U.S. citizens, during the WWII era was justified for racial, cultural, political, legal, or economic reasons after reading historical texts and documentation.

Students will:

- Evaluate various explanations for actions or events and evaluate authors’ differing point of views on the same historical event.

- Integrate and evaluate multiple sources of information to address a question or solve a problem.

- Construct a thesis statement and write an argumentative paper that uses contextual evidence from the text to support their stance.

- Analyze the events that led to the relocation of Japanese Americans into the incarceration camps during the World War II era.

- Explain Fred Korematsu’s actions in response to Executive Order 9066 and why he challenged the government in court over his treatment.

- Recount what legal basis the verdict of Fred Korematsu v. United States was determined in 1944 and how it was appealed and overturned in 1983.

- “Americans in Concentration Camps” The Crisis excerpt Article

- Document Analysis Worksheet

- “Four Primary Source Documents: Japanese Incarceration”

- Four-Four-Two, F Company at War Film (Run time: 27 minutes 38 seconds)

- How to Write an Argumentative Paper

- Japanese Relocation newsreel (Run time: 9 minutes 28 seconds)

- Korematsu v. United States Supreme Court Ruling excerpt

- Motion Picture Analysis Worksheet

- “One Man Seeks Justice from a Nation: Korematsu v. U.S.” Abridged Version

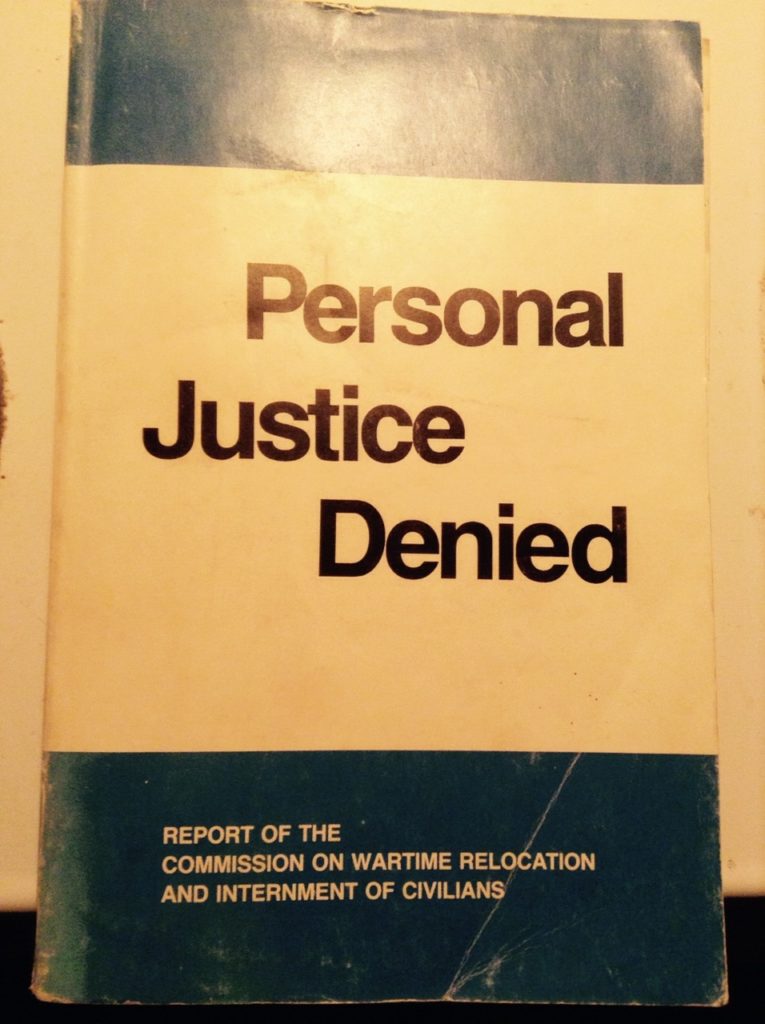

- “Personal Justice Denied” excerpt

- The Nisei: The Pride and the Shame Film

- Transcript of Executive Order 9066 Poster

- What led to and allowed for the relocation of Japanese Americans into incarceration camps?

- What were the reactions to Japanese American incarceration? Think about how reactions differed within and across different groups (Japanese Americans, White Americans, Black Americans, etc.).

- How did the government justify the incarceration of Japanese Americans? In what ways do you agree and/or disagree with that reasoning?

This lesson can be implemented to fit various instructional schedules. Here are three different options:

- Three instructional sessions:

- Day 1: Complete Lesson 1, and provide some time during class for students to skim the Korematsu story from Lesson 2. Assign the story as homework, answering questions about unfamiliar words, concepts, ideas that are necessary to understand to complete the homework.

- Day 2-3:Complete Lesson 2 over the course of two instructional sessions and conclude with a classroom discussion on the provided discussion questions. You may choose to assign an individual writing assessment based on one of the discussion questions as well or instead.

- One week:

- Day 1: Complete Lesson 1, and provide some time during class for students to skim the Korematsu story from Lesson 2. Assign the story as homework, answering questions about unfamiliar words, concepts, ideas that are necessary to understand to complete the homework.

- Day 2-3: Complete Lesson 2 over the course of two instructional sessions and conclude with a classroom discussion on the following prompt (from Socratic Seminar of Lesson 3): “Was the reasoning for Japanese Americans incarceration justified?” For homework, have students review How to Write an Argumentative Paper and write the thesis statement for their paper.

- Day 4-5: Complete a shortened version of Lesson 4, spending very little class time on how to write an argumentative paper and substantially less time on in-class essay writing.

- Between one and two weeks:Complete the unit as outlined, spending the full suggested time on discussing how to write argumentative papers and in-class essay writing and editing for Lesson 4 (which would stretch that lesson to take up several days of instruction).

- Assimilated: to absorb into the cultural tradition of a population or group

- Espionage: spying or using spies to get information about a competitor or foreign government

- Exclusion: to bar from participation, consideration, or inclusion

- Fundamental: of central importance, deep-rooted

- Internment: being interned, or held, against one’s will or choice; some refer to Japanese American internment as “incarceration” instead because of its similarities to conditions of imprisonment

- legislative: belonging to the branch of government that is charged with such powers as making laws

- Lynching: to put to death (as by hanging) by mob action without legal approval or permission

- Precedent: something done or said that may serve as an example or rule to authorize or justify a later act of the same or similar kind

- Prejudice: a hostile opinion or leaning formed without just grounds or before sufficient knowledge

- Surveillance: close watch kept over someone or something, typically due to feelings of distrust

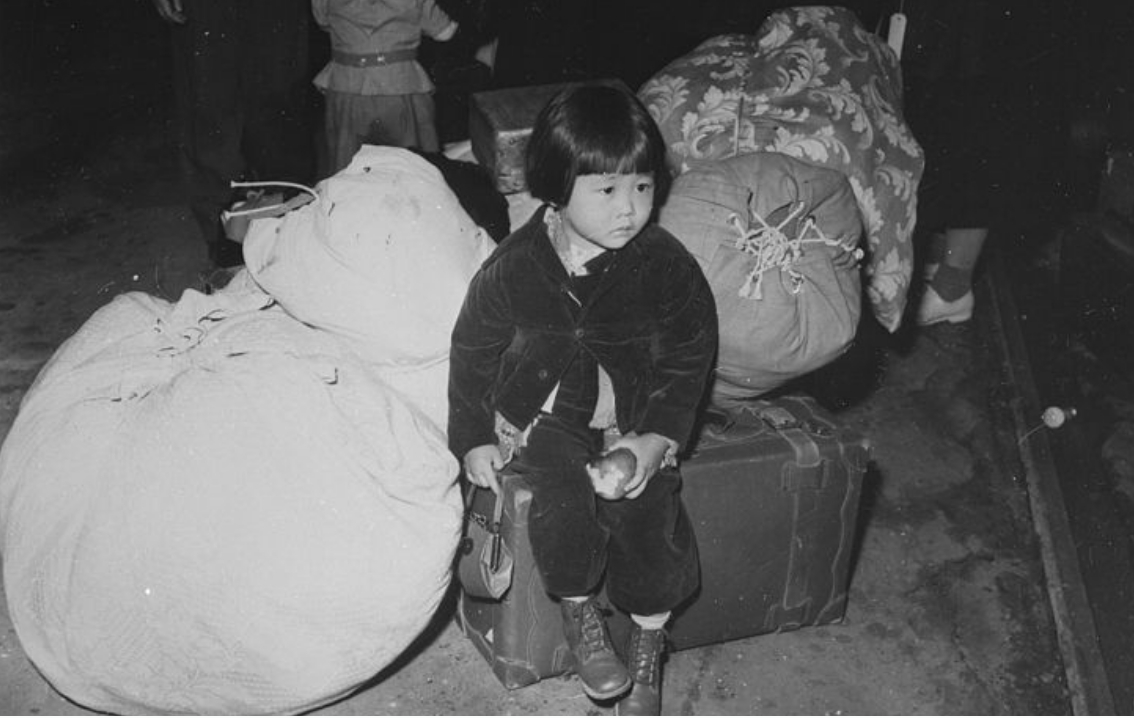

Two-year-old Yuki Okinaga Hayakawa waits at Union Station in Los Angeles, for the train taking her and her mother to Manzanar (April 1942).

Image Credit: U.S. Department of the Interior (public domain image)

Source

LESSON 1:

Racial Profiling (Suggested Time: 30 minutes)

Activity: Racial Profiling

- Begin by writing any (or all) of the following prompts listed below, on the board:

- You are in a convenience store and notice that two teenagers enter at the same time. One is white; the other is black. The store manager seems really nervous at the presence of the black teenager and closely monitors his every movement while ignoring the activities of the white teenager.

- A Latino family is travelling together in a van on their way to a vacation spot when they are pulled over by the police because one of their brake taillights is broken. When police officers notice the family in the van, they immediately ask for verification papers of their U.S. resident legal status.

- A Sikh man wearing a turban enters an airport security checkpoint and is immediately pulled aside and detained without explanation. His belongings are subsequently thoroughly inspected and he undergoes heavy questioning before he is allowed to board the plane.

- Instruct students to write what their initial impressions and/or feelings would be if they were to witness the above situation(s) listed and why. Students should write at least 2-3 sentences for each prompt.

- Next, have an open class discussion asking for volunteers to share what they have written with the rest of the class. Encourage students to share other examples of racial profiling they have witnessed as a means to stimulate interest and participation in the topic. Discussion should last about 5 to 8 minutes.

- After the discussion, ask students the following question: “What would you do if it was the President of the United States that had you detained based solely on your racial profile? Do you think this is possible?” After engaging student responses, lead into the fact that there was indeed a time in the United States’ past where this actually happened. Briefly introduce the Korematsu story.

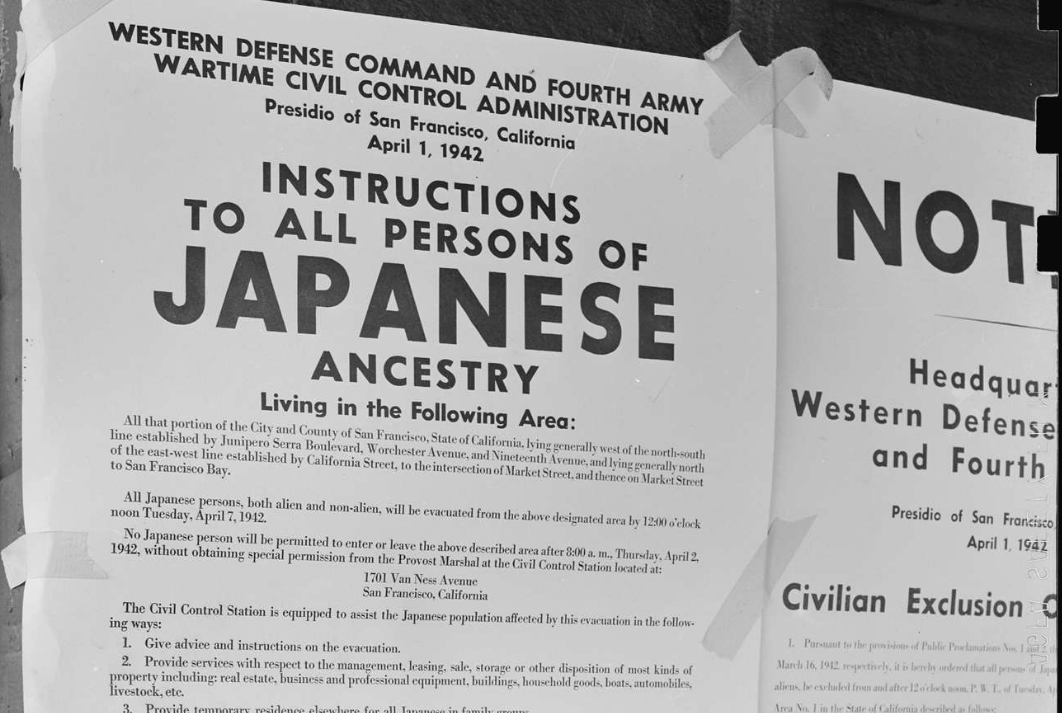

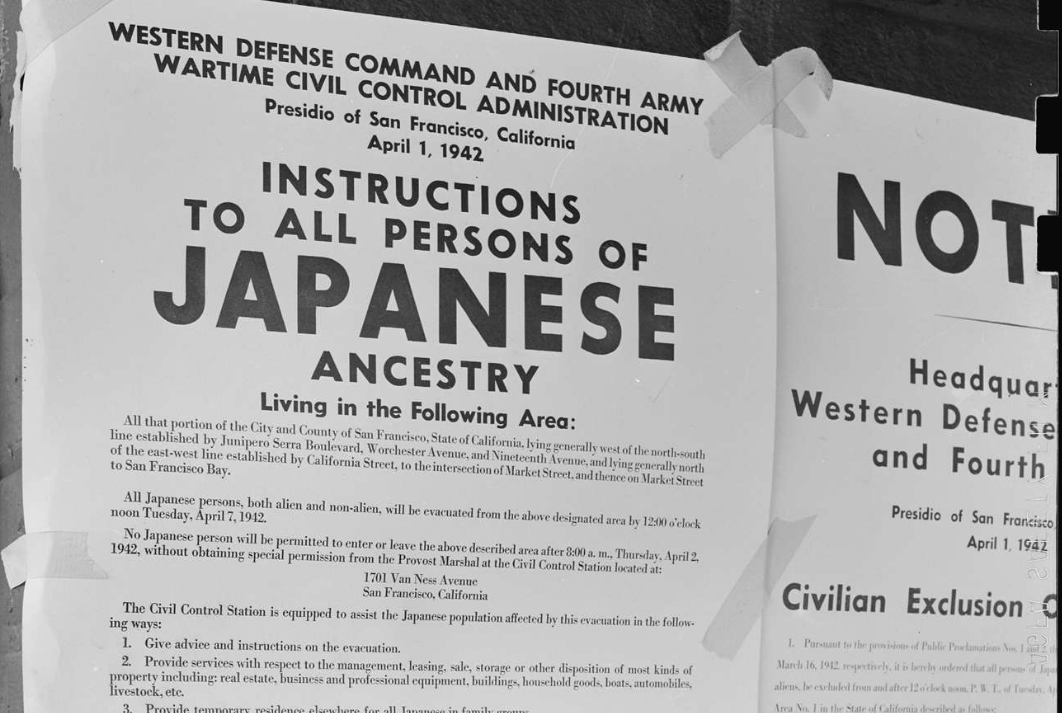

Executive Order 9066 poster directing the removal of persons of Japanese ancestry

Photo Credit: Records of the War Relocation Authority (public domain image)

Source:

DOCSTeach

LESSON 2: Analyzing Source Documents (Suggested Time: 100 minutes plus homework)

Materials:

- “Americans in Concentration Camps” The Crisis excerpt

- “Document Analysis Worksheet”

- Four-Four-Two, F Company at War Film (Run time: 27 minutes 38 seconds)

- “Four Primary Source Documents: Japanese Incarceration”

- Japanese Relocation newsreel (Run time: 9 minutes 28 seconds)

- Korematsu v. United States Supreme Court Ruling excerpt

- Motion Picture Analysis Worksheet

- “One Man Seeks Justice from a Nation: Korematsu v. U.S.” Abridged Version

- “Personal Justice Denied” excerpt

- Transcript of Executive Order 9066

Activity: Justifying and Opposing Japanese American Incarceration

- Have students read and annotate the Korematsu story (“One Man Seeks Justice…”). Be sure to ask students which terms, concepts, ideas are unfamiliar and lead students to a better understanding by providing definitions / explanations or facilitating a class discussion, as needed.

- Next, play the Japanese Relocation newsreel by U.S. Office of War Information, 1943 http://www.archive.org/details/Japanese1943 (Run Time: 9 minutes 28 seconds). After students have viewed the newsreel and filled out their “Motion Picture Analysis Worksheet” (individually or in pairs), have a brief class discussion about the film and students’ responses in their worksheet.

- Introduce the Document Analysis Worksheet to the students. Explain how to fill out a Document Analysis Worksheet and inform students that they will be completing one for each primary/secondary source they read in this unit.

- Play The Pride and the Shame https://archive.org/details/75944HistoryOfUSForeignRelationsPT4 (Run time: 30 minutes 32 seconds). This is a documentary film about the Japanese incarceration and the brave actions of patriotic Japanese-Americans. Daniel Inouye bravely served in the U.S. Army as part of the 442nd during WWII.

- Instruct students to fill out their Motion Picture Analysis and Document Analysis Worksheets for the film.

- Introduce the primary/secondary sources one at a time in the order listed below. Have students complete a Document Analysis Worksheet for each one. If possible, each student should have a copy of every primary/secondary source assigned for reading.

- If students do not have practice analyzing documents, this should be modeled for them. There are a total of eight sources in addition to the two videos available for use in this unit and are labeled below with the following:

- F-argues in favor of Japanese Incarceration

- A-argues against Japanese Incarceration

- F/A-can be used to argue either position

- Depending on how much time / resources you have available for the unit, you can use however many primary / secondary sources you deem necessary. It is recommended that you use at least 3 sources.

Sources:

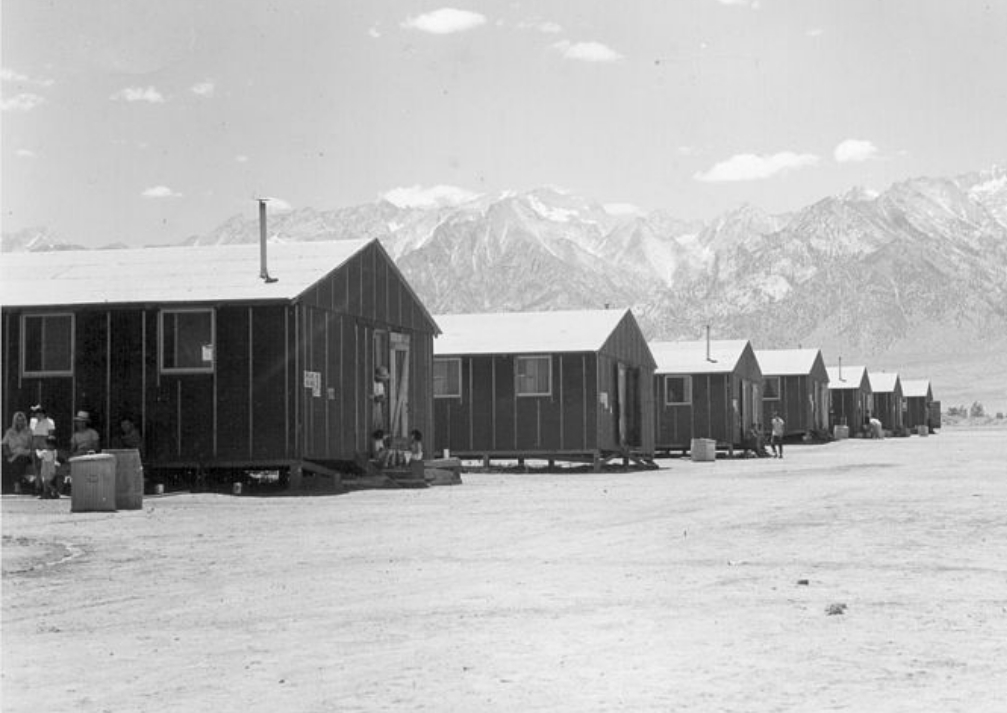

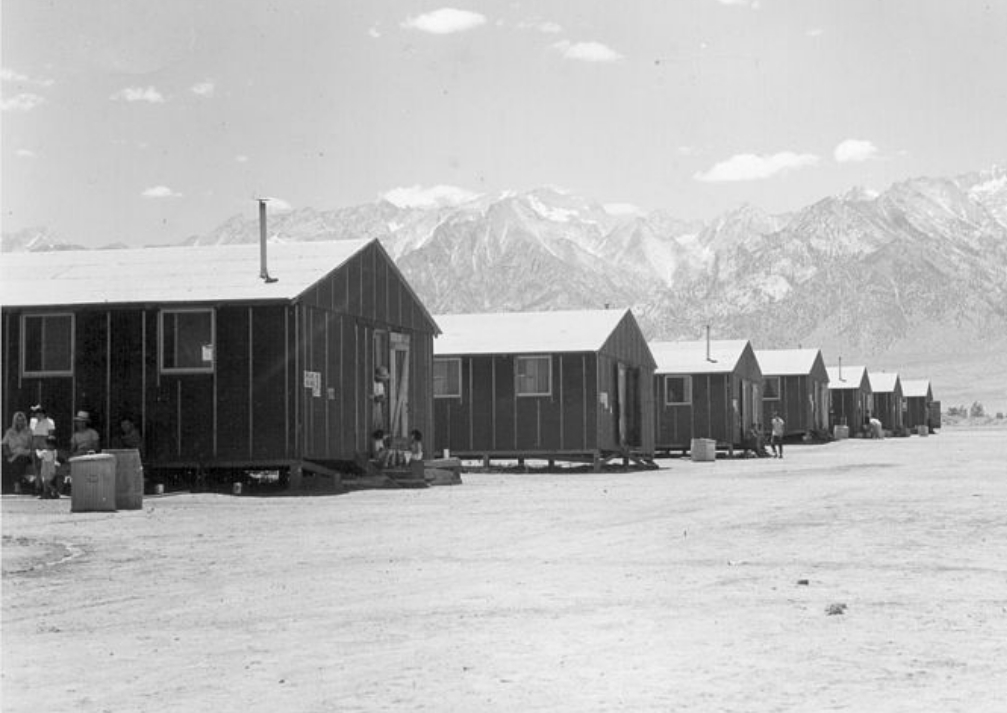

Manzanar Relocation Center, 1942

Photo Credit: Dorothea Lange (public domain image)

Source

LESSON 3:

Crafting an Argument on Japanese American incarceration (Suggested Time: 30 minutes plus homework)

Materials:

- Copies of the primary/secondary sources

- Document Analysis Worksheet

Activity: Socratic Seminar

- Have students prepare their own questions from the source documents before the Socratic Seminar.

- Ask the students to form a circle.

- Ask students to focus the discussion on whether the reasoning for Japanese Americans incarceration is justified. Inform students to write down their thesis statement for their argumentative paper at the end of the discussion.

- Encourage students to listen carefully and take notes. Remind students of the Socratic Seminar rules:

- Speak so that all can hear you.

- Listen closely.

- Speak without raising hands.

- Refer to the text.

- Talk to each other, not just to teacher.

- Ask questions. Don’t stay confused.

- Invite and allow others to speak.

- Respect other peoples’ viewpoints and ideas.

- Know that you are responsible for the quality of the conversation.

- Interact to add new ideas to the discussion when the discussion needs to be invigorated.

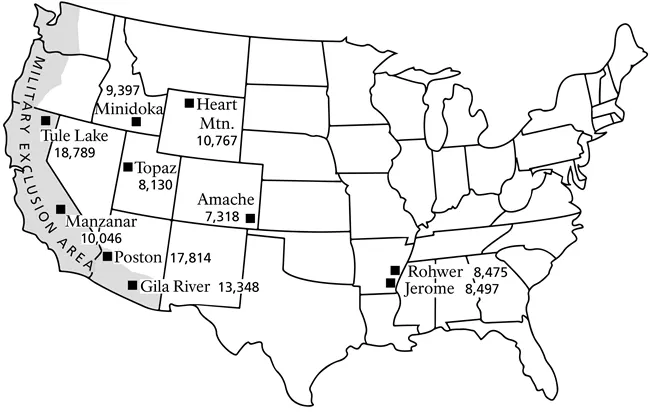

Japanese Americans Incarceration camps, "War Relocation Centers" and their peak populations.

Source:

National Park Service

LESSON 4:

Writing an Argumentative Paper (Suggested Time: 60 minutes plus homework)

Materials:

- Copies of the primary/secondary sources

- Document Analysis Worksheet

- How to Write an Argumentative Paper

Activity: Essay Writing

- The instructor describes what an argumentative paper is and how to write one. A guide detailing how to write an argumentative paper – How to Write an Argumentative Paper – is provided in the unit. Students should be given a copy of the guide to help them construct their papers.

- This process can be brief or take several days depending on students’ prior experience with writing papers.

- Having at least one full class period for this explanation is recommended.

- Students begin their first drafts of their argumentative papers. This phase should incorporate at least two days (if not more) for the writing process. Students should be encouraged to work on this at home as well as in the classroom for best results.

- Once the first drafts are complete, have students form groups of 3-4 and students read and peer-edit each other’s drafts. Using the guide on how write an argumentative paper, as well as instructions from the instructor, each student should identify which elements are good and which can be improved in each draft.

- Once feedback has been given from the peer editing session, students will write their final drafts of the argumentative paper.

Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. Personal Justice Denied. University of Washington Press. San Francisco and Washington, D.C. :1997.

Howard, Harry Paxton. “Americans in Concentration Camps,” The Crisis, September 1942.

California Common Core Standards Addressed

Reading Standards for Literacy in History/Social Studies:

RH 11-12.1:

Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources, connecting insights gained from specific details to an understanding of the text as a whole.

RH 11-12.3:

Evaluate various explanations for actions or events and determine which explanation best accords with textual evidence, acknowledging where the text leaves matters uncertain.

RH 11-12.6:

Evaluate authors’ differing points of view on the same historical event or issue by assessing the authors’ claims, reasoning, and evidence.

RH 11-12.7:

Integrate and evaluate multiple sources of information presented in diverse formats and media (e.g., quantitative data, video, multimedia) in order to address a question or solve a problem.

RH 11-12.8:

Evaluate an author’s premises, claims, and evidence by corroborating or challenging them with other information.