1.6.2 - The Ghadar Movement: Fighting Colonialism at Home and Abroad

This content was created using source materials from the South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA). All lesson plan content is owned by The Asian American Education Project (AAEdu). As such, users agree to attribute all work to The Asian American Education Project and South Asian American Digital Archive.

Grade: 9-12Subject:

History, Social Studies, English Language Arts

Number of Lessons/Activities: 5 + Extension Activities

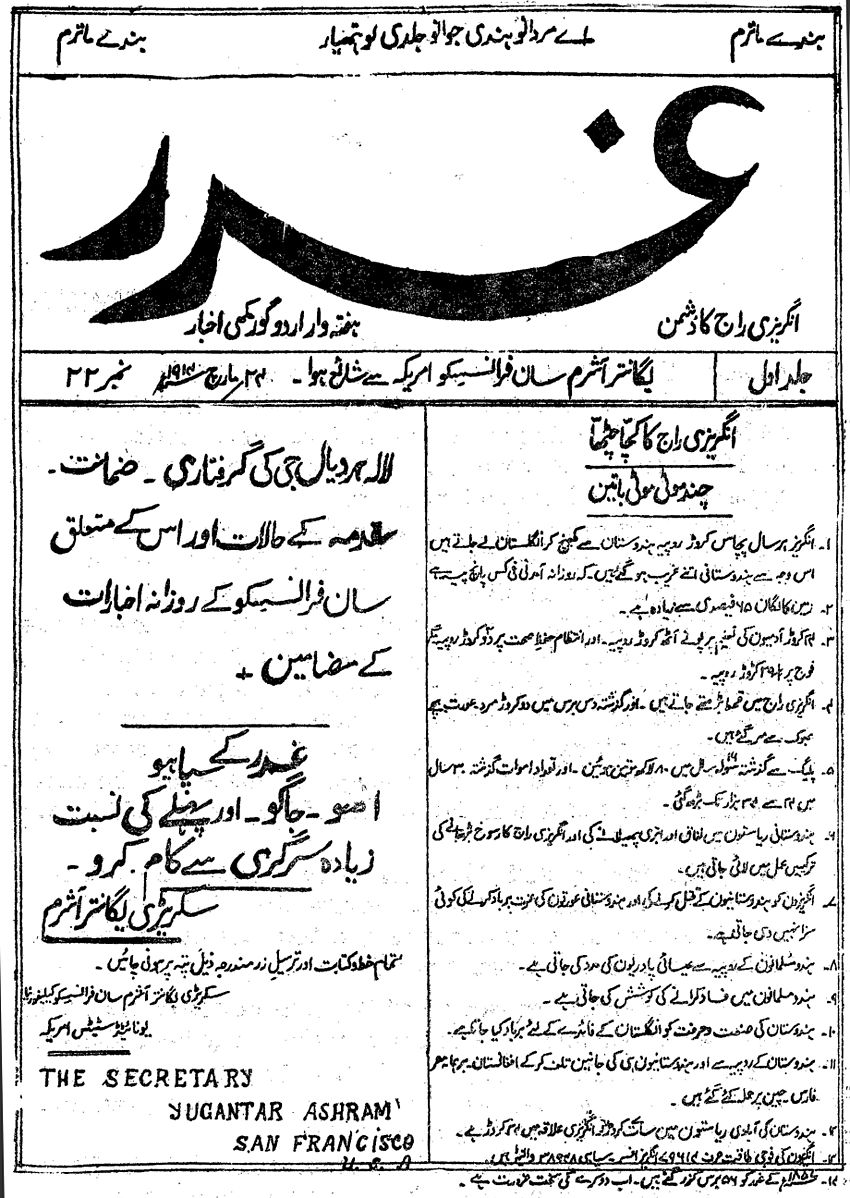

The ability to mass produce publications has allowed for messages to spread beyond an individual's local area. The Ghadar Party, established in 1913 in San Francisco, California, was born out of a need to advocate for a free India. The South Asian diaspora was brought together to fight against the injustices rooted in British rule and colonial beliefs and practices. One avenue of advocacy the Ghadar Party utilized was a newspaper titled The Hindustan Ghadar. One of the goals of Ghadar was to have readers distribute copies of the newspaper to individuals within the Indian diaspora and those who continued to live in India. This lesson will cover the importance of publications in finding the voice of and building support for movements.

Students will:

- Utilize observing and questioning skills in order to better understand the motives and impact of the Ghadar Party

- Gather strategies and inspiration from Ghadar and other publications as a message sharing tool

The Ghadar Movement: Fighting Colonialism at Home and Abroad Essay:

Excerpt from Our Stories: An Introduction to South Asian America

“The Ghadar Party” by Seema Soh

© SAADA

In November 1913, a group of Indian

revolutionaries gathered at their newly established headquarters on a San Francisco hilltop to raise a red, yellow, and green flag that represented freedom, brotherhood, and equality—the values of the free India they envisioned. These men were members of the

Ghadar Party, a group of Indians who sought to overthrow the British

Empire through armed revolution. On November 1, the party announced its emergence to the world by launching its first newspaper,

Ghadar. In its inaugural issue, the paper boldly declared that “today there begins in foreign lands, but in our country's language, a war against the English

Raj . . . What is our name? Ghadar. What is our work? Ghadar. Our name and our work are identical.”

In less than a year, the party claimed to have thousands of members and dozens of branches across the world, including in Vancouver, Portland, Astoria, St. John, Sacramento, Stockton, Panama, Manila, Hong Kong, and Shanghai. Additionally, the party began circulating twenty-five hundred copies of

Ghadar in

Gurumukhi and twenty-two hundred in

Urdu each week. Within six months, the paper had reached India, China, Japan, Manila, Sumatra, Fiji, Java, Singapore, Egypt, Paris, South Africa, British East Africa, and Panama.

The Ghadar Party was a coalition of

Punjabi migrant workers and

Bengali and Punjabi intellectuals and students that emphasized

secularism and unity despite linguistic, religious, and regional differences. Though its core leadership was

Hindu,

Sikh, and

Muslim, nearly 90 percent of its membership was Punjabi Sikh men, almost half of whom were veterans of the British Indian Army and whose loyalty and service to the empire was presumed by British officials. What united these seemingly disparate groups was their common belief that they had been pushed out of India because of

colonialism and now experienced a shared sense of humiliation as degraded colonial subjects across the world. Racial discrimination and violence in North America produced an anti-colonial consciousness among them, and the party’s goal of an independent India was inseparable from attaining racial equality abroad.

Ghadar exhorted readers that it was their patriotic duty to circulate copies of the paper among as many Indians as possible. Indians across the

diaspora who received copies of the paper were asked to send them on to friends in India after reading them in order to help spread the party's message. In spite of British efforts to prohibit the circulation of

Ghadar, the paper continued to reach India from the Pacific coast of North America via Shanghai, Hong Kong, Nairobi, Johannesburg, Singapore, Manila, Bangkok, Tientsin, and Moji. When the first issue arrived in India on December 7, 1913, it was immediately banned, and officials in India began searching all luggage from the United States and East Asia and seizing any Ghadar Party publications. However, the contents of the paper still made their way into India. Once Indians became aware that authorities were on the lookout for the weekly periodical, they began hiding small cuttings and sending handwritten excerpts from the paper in private letters.

At the outbreak of the First World War, the Ghadar Party launched into action, heeding the call of their leaders, who proclaimed that the need for British troops in Europe presented an opportune moment to organize

uprisings in both India and British

imperial outposts. Between 1914 and 1918, the party mobilized nearly eight thousand Indians from North and South America and East Asia to return to India to overthrow British rule. Anticipating their return, British officials arrested hundreds of

Ghadarites before they ever disembarked from the ships that carried them home, dealing a severe blow to the party’s plans. Those who were not detained quickly made contact with Indian revolutionaries across the country and fixed February 21, 1915, as the day that simultaneous uprisings would erupt across India. The uprisings would center on convincing Indian soldiers to strike against British officials first, thereby inspiring the masses to rise up and overthrow British rule. Ghadarites visited military

cantonments to recruit soldiers, arguing that Indian military service perpetuated the status of Indians as slaves to the empire and as pawns used to slaughter the world’s colonized peoples and reinforce the brutality of British rule. Party members also gathered arms, produced flags, and collected materials for destroying railways and telegraph wires, looting treasuries and distributing arms and ammunitions. Their plans, however, never came to fruition, due to the workings of British

intelligence.

Although Ghadarites believed that their successful efforts in recruiting Indians in the United States would generate the same kind of enthusiasm in India, they discovered that India was not as ripe for revolution as they had hoped. Leaders of the Indian National Congress, priests of several important Sikh

gurdwaras, and many nationalist leaders in India strongly denounced the party. While Ghadarites in North America successfully highlighted the interconnectedness of

colonialism, racial subjugation, and economic exploitation to mobilize thousands along the Pacific coast, they were ultimately unable to convince their countrymen in India to join them.

Bibliography:

Sohi, Seema (2021). The Ghadar Party. Our Stories: An Introduction to South Asian America, South Asian American Digital Archive.

- Bengali: the modern Indo-Aryan language of Bengal, a region in eastern India

- Cantonment: a military station

- Colonialism: the control of a people or land by a foreign nation

- Diaspora: individuals who have moved away from their ancestral homeland

- Empire: a political unit in which one nation has multiple territories under its authority

- Ghadar3: a Punjabi and Urdu word that translates to “mutiny,” the Ghadar Movement was a group of Indians who sought to overthrow the British Empire through armed revolution

- Ghadarites: active participants of the Ghadar Movement

- Gurdwara: a Sikh shrine or place of worship

- Gurumukhi (or Gurmukhi): the alphabet or script used in Punjabi

- Hindu2: the dominant religion of India that is widely considered the world's oldest religion, with traditions originating around 8,000 years ago, comprising approximately 79.8% of India’s population

- Imperialism: the extension of power of a nation by direct acquisition of land

- Intelligence: information concerning an enemy or possible enemy

- Muslim2: a religion that was founded by the prophet Muhammad in Mecca in the early 7th century CE, comprising approximately 14.2% of India’s population.

- Punjabi: an Indo-Aryan language of the Punjab, a region in northern India

- Raj: the period of British rule in India, 1858-1947

- revolutionary: a person advocating for radical change

- Secularism: indifference to or rejection or exclusion of religion

- Sikh2: a religion that originated in India during the 15th century, comprising approximately 1.7% of India’s population

- Uprising: an act or instance of rising up, usually in defiance of an established government

Uprising: an act or instance of rising up, usually in defiance of an established government

- Urdu: an Indo-Aryan language that is widely spoken in Pakistan and India

- Zine: homemade, informal publication on a specific topic

Instruction Consideration:

This mini unit is not intended to be completed in one instructional session. It is a resource for educators to implement as they see fit. AAEdu recommends focusing on the discussion questions and instructional activities if teaching in a shorter period (one to two instructional sessions.) Incorporate one or more extension activities if using a longer period (five or more sessions.)

- What were the goals of the Ghadar Party?

- How did the Ghadar Party's actions impact the world at the time?

- What can we learn from the work of the Ghadar Party?

- How did the Ghadar Party start and maintain a movement?

- How did the Ghadar Party use the media to spread their ideas or messages?

Printed newspapers were a common source of news when the Ghadar Party was active. Today, there are many more sources for people to get the news.

Credit: Photograph by Hatice Yardim free to use under the Unsplash License

Source

Activity 1: How Do You Get Your News?

- Ask students to think about how they get their news. Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- How do you get your news?

- What are your news sources?

- What type of news are you getting?

- Ask students to think about how the media is used to support movements. Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- What are some recent movements you can think of? How do they grow?

- What role does the media have in sharing ideas or messages? What examples can you think of?

Activity 2: Primary Source Analyses

- Primary Source #1: Project/share the following primary source: “A new problem for Uncle Sam” from the San Francisco Call

- Ask students to generate three things they notice, two inferences they can make, and one question they have.

- Provide the following sentence stems if needed:

- I notice _____________.

- I can infer _________ because _______.

- Why/who/when/where/what/how…?

- Primary Source #2: Project/share the following primary source: “India in America” by Har Dayal

- Have students read the excerpt in small groups.

- Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- What are the similarities between the two sources?

- What are the differences between the two sources? What accounts for the differences?

- What connections can you make to other historic moments?

Present day image of the Yugantar Ashram in San Francisco, which was the headquarters of the Ghadar Party. In 1975, the building was turned into the Ghadar Memorial.

Credit: "

Yugantar Ashram by

Ragesoss is licensed under

CC BY-SA 3.0.

Source

Activity 3: Ghadar Party Essay & Silent Conversations

- Distribute the essay entitled “The Ghadar Party” to students. Depending on the needs of your class, you can either read as a class, in small groups, independently, or mixed (some groups, some independent).

- Have students complete the Note-Taking Worksheet, annotating the text as they go. (If students need more structure or guidance for annotating, use the Ghadar Party Reading Guide.)

- Place the Ghadar Party - Silent Conversation pages around the room.

- Introduce students to the concept of the Silent Conversation. (The goal of this practice is for everyone to share and develop their thoughts on the topic at the same time.)

- Direct students to move around the room and silently interact with the different prompts.

- Direct students to write an answer to the question/prompt on the page or write a comment that interacts with a classmate’s comment. Give them ten minutes to complete this task.

- After students have interacted with each conversation page, give students a few minutes to silently revisit the conversation strands to read what was added after their interaction with each prompt.

- Facilitate a discussion by reviewing the prompts. (Read out each question or ask students to share questions that stood out to them.):

- What additional thoughts or questions do you have about “A new problem for Uncle Sam”?

- What additional thoughts or questions do you have about “The Modern Review”?

- What were the goals of the Ghadar Party?

- How did the actions of the Ghadar Party impact the world at the time?

- What connections can you make between the Ghadar Party and other moments in history?

- How and what can we learn from the work of the Ghadar Party?

- Have students complete a quick-write given these prompts:

- What are some responses that stood out to you or surprised you?

- Are there any thoughts that you don’t agree with? Are there any thoughts that you do agree with? Why?

- What roles does the media play in spreading ideas and messages?

- What is something you took from this activity?

- Tell students that they will revisit the “conversations” again at the end of the lesson.

Activity 4: Researching Community Organizing through Publications

The Ghadar Party published

Ghadar in order to spread their message across the South Asian diaspora. Students can create a zine -- a homemade, informal publication on a specific topic -- on the Ghadar Party to highlight the history of the party and the strategies they used to spread their ideas.

Credit: "

collage & art journal ideas zine by

katie licht is licensed under

CC BY 2.0.

Source

Activity 5: Student Zine Creation: Ghadar Movement

- Students can now revisit everything they have learned about the Ghadar Party and the strategies different groups have utilized in order to spread their cause or ideas.

- Distribute the Ghadar Party Assessment and have students choose one of the following assessment options:

- Write an essay about what the Ghadar Party was, what their goals were, and the strategies they used to spread their ideas. Discuss how the use of regular publications affected the impact of the Ghadar Party. Compare and contrast those strategies to the strategies of other groups.

- Create an infographic or graphic zine about the Ghadar Party. Make sure to highlight the history of the party and the strategies they used to spread their ideas. Include how the use of regular publications affected the impact of the Ghadar Party and some tips on how to best spread a message through a publication.

- To close, have students revisit their Silent Conversations.

- Give students ten minutes to interact with the prompts once more.

- Facilitate a discussion by asking “How have your thoughts and ideas changed since doing additional research and creating your own zines?”

- Option 1: Student Zines

- This project can be done in groups or independently. It can be as developed as you see fit, ranging from a simple draft plan to a complete zine ready for local distribution.

- Have students fill out the Student Zine Planner.

- Encourage students to create zines by utilizing various mediums such as digital tools.

- Have students present their zines to the class. (Students can also attempt to distribute their zines to their local community.)

- Have students write a reflection about how their zine connects to strategies utilized by the Ghadar Party.

- Option 2: Copy Change/Mentor Text Poem

- If They Ask You Who You Are by Kartar Singh Sarabha is featured in the Ghadar Party essay from South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA). Kartar Singh Sarabha was one of the Ghadar Party’s leading activists. In creating a copy change of this poem, students will experience how poetry can be used to convey messages of a movement.

- Have students read If They Ask You Who You Are.

- Have students discuss the meaning behind the poem.

- Have students use the poem as a mentor text and create a copy change poem using the If They Ask You Who You Are Copy Change Poem Worksheet .

National Standards for History:

Historical Thinking Standard 2: The student comprehends a variety of historical sources. Therefore the student is able to:

- Identify the author or source of the historical document or narrative.

- Read historical narratives imaginatively, taking into account what the narrative reveals of the humanity of the individuals and groups involved–their probable values, outlook, motives, hopes, fears, strengths, and weaknesses.

- Appreciate historical perspectives–the ability (a) describing the past on its own terms, through the eyes and experiences of those who were there, as revealed through their literature, diaries, letters, debates, arts, artifacts, and the like; (b) considering the historical context in which the event unfolded–the values, outlook, options, and contingencies of that time and place; and (c) avoiding “present-mindedness,” judging the past solely in terms of present-day norms and values.

Historical Thinking Standard 3: The student engages in historical analysis and interpretation. Therefore, the student is able to:

- Compare and contrast differing sets of ideas, values, personalities, behaviors, and institutions by identifying likenesses and differences.

- Draw comparisons across eras and regions in order to define enduring issues as well as large-scale or long-term developments that transcend regional and temporal boundaries.

Historical Thinking Standard 5: The student engages in historical issues-analysis and decision-making. Therefore, the student is able to:

- Identify issues and problems in the past and analyze the interests, values, perspectives, and points of view of those involved in the situation.

College- and Career-Readiness Anchor Standards (CCSS):

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.1

Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.2

Write informative/explanatory texts to examine and convey complex ideas and information clearly and accurately through the effective selection, organization, and analysis of content.